10 Dec 2020

Soundings: Marking Time

-

Sasha Kow

MusicianSasha Kow is a Malaysian composer based in Vancouver. She completed her BMus in Composition at the University of Oregon, and is currently in her second year of her Master of Music in Music Composition at the University of British Columbia. Her work strives to understand where and how her background and upbringing fit into the world of Western contemporary art music. Through her involvement with the Score Cluster Research, she seeks to diversify her approach to writing music and hearing sound.

Read More

-

Athena Loredo

Musician and ComposerAthena Loredo is a composer based in Vancouver. She grew up in Newfoundland and obtained a BMus (Hons) in composition from Memorial University. Currently, Loredo is completing a Master’s in Composition at the University of British Columbia. Her compositional style is influenced by the manipulation of musical fragments. From quoting Bach, Prokofiev and Dvorak in a symphonic poem to creating variations on a Mexican folk song, Loredo explores combinations of timbres and melodic fragments, reworking music to create something new.

Read More

-

Joseph Stacy

MusicianJoseph Stacy is from the United States, having grown up in the Appalachian community of Pulaski, Virginia. He graduated summa cum laude from Ohio University in 2019 with a BMus in Piano Performance and Pedagogy. He is currently in his second year of the Master of Music in Piano Performance at the University of British Columbia, where he is a student of Mark Anderson. In addition to his performance career, Stacy has presented at multiple state and national conferences throughout the US on subjects ranging from performance health to equitable access of music involvement. Stacy seeks social justice engagement through his work as a performer, pedagogue and scholar by pursuing interdisciplinary projects that are culturally relevant and dismantle colonialist norms persisting throughout North American society.

Read More

-

Olivia Whetung

ArtistOlivia Whetung is anishinaabekwe and a member of Curve Lake First Nation. She completed her BFA with a minor in anishinaabemowin at Algoma University in 2013, and her MFA at the University of British Columbia in 2016. Whetung works in various media including beadwork, printmaking, and digital media. Her work explores acts of/active native presence, as well as the challenges of working with/in/through Indigenous languages in an art world dominated by the English language. Her work is informed in part by her experiences as an anishinaabemowin learner. Whetung is from the area now called the Kawarthas, and presently resides on Chemong Lake.

Read More

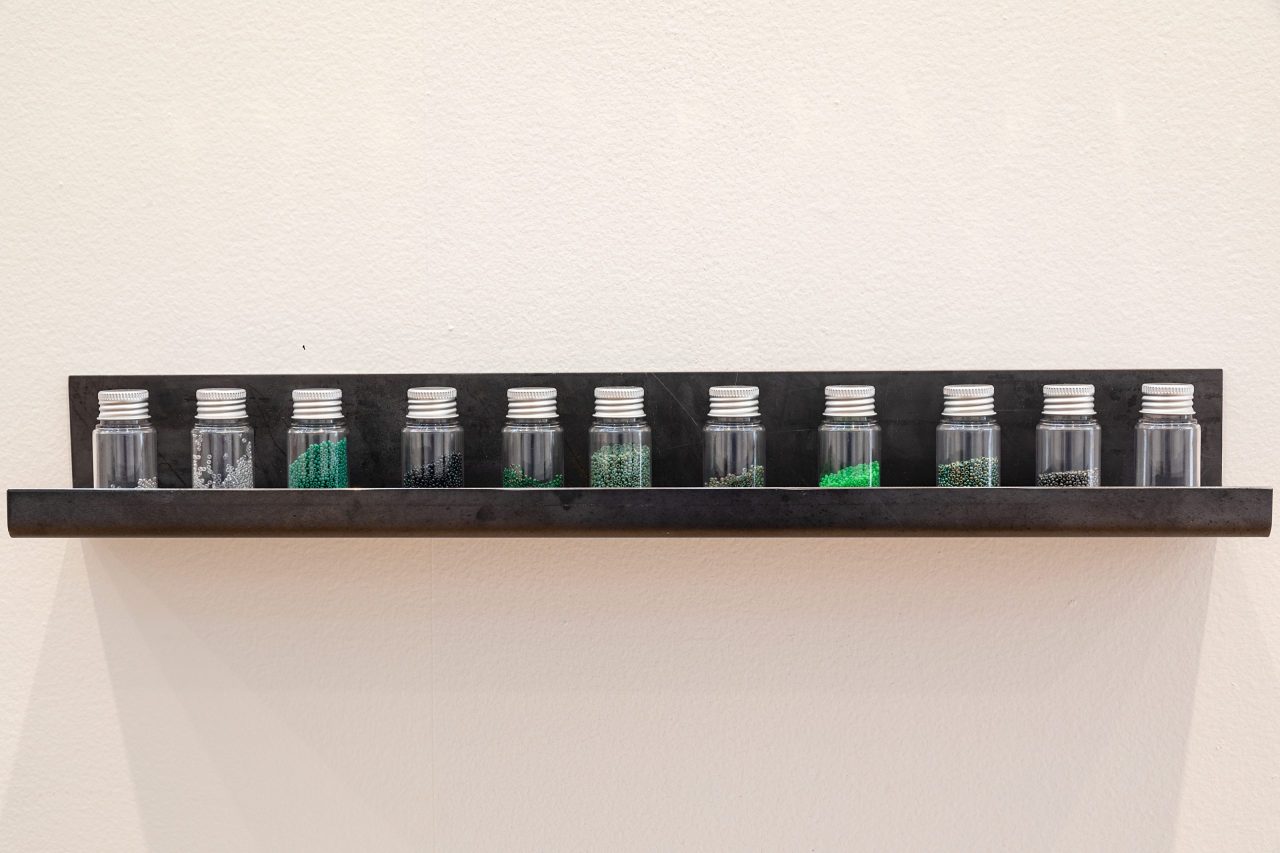

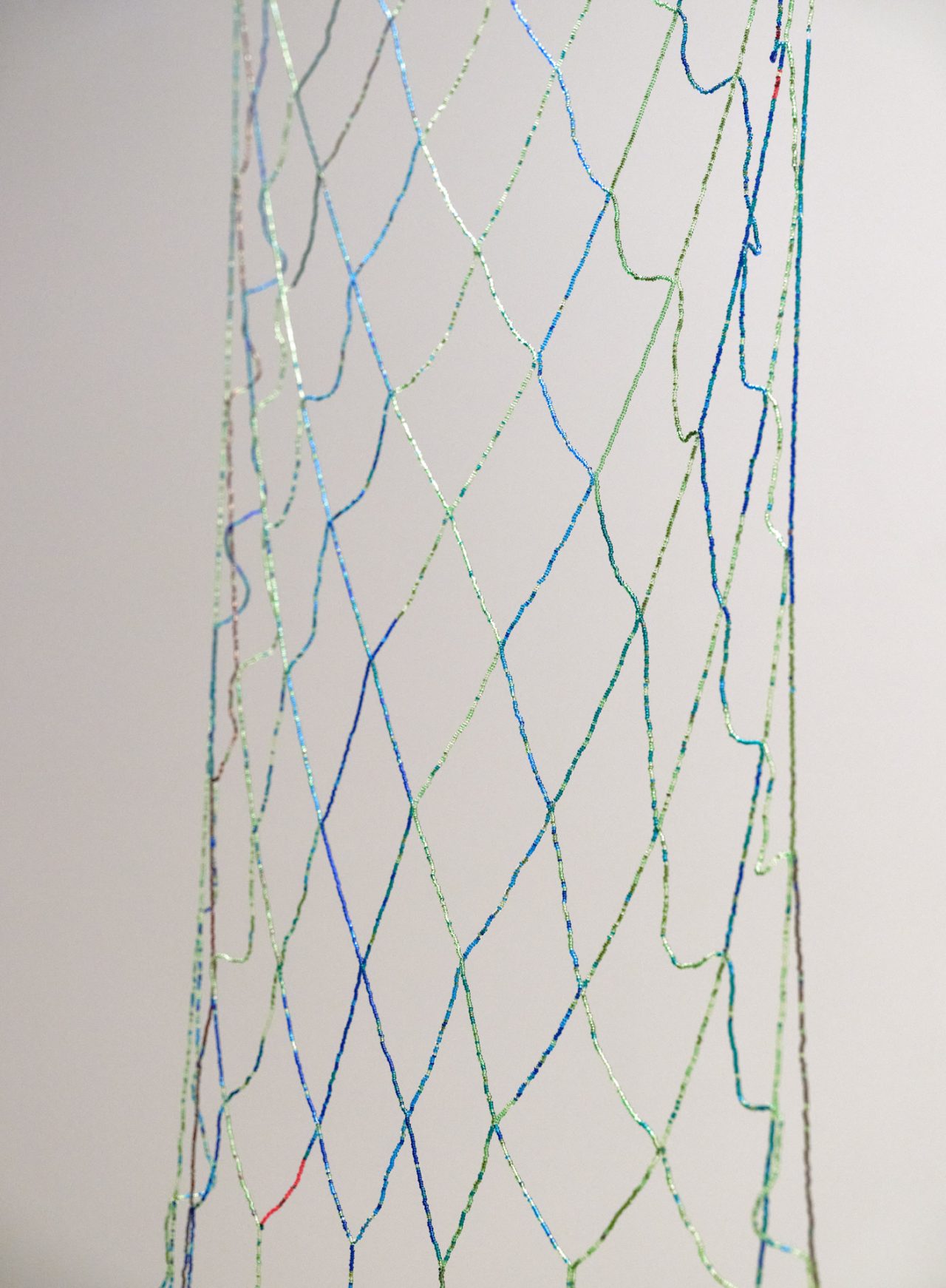

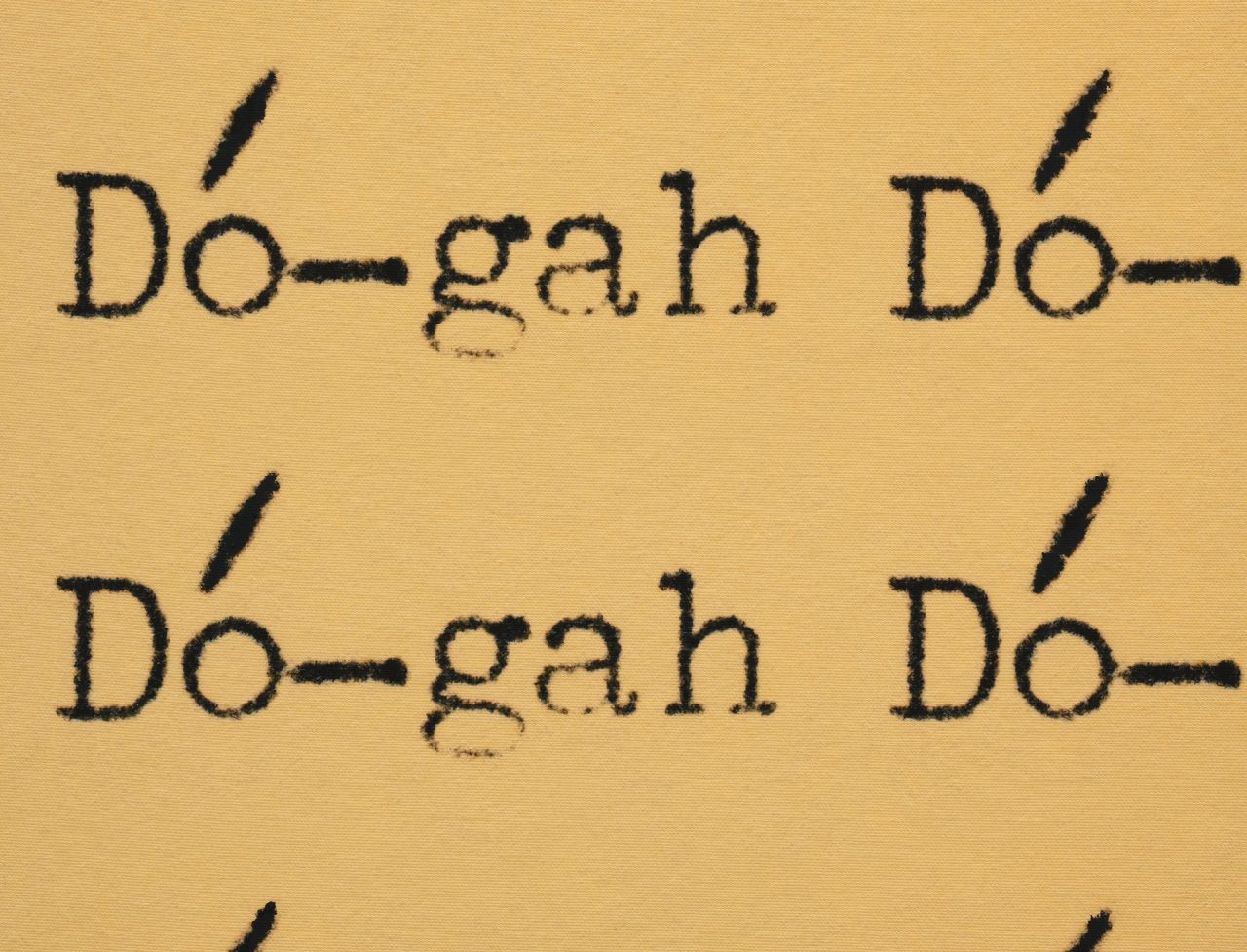

In the works of Olivia Whetung, time is represented across the full spectrum of occurrence, from the immediate response of a viewer to the slow and evolving layering of geological forces. Her installation for Soundings: An Exhibition in Five Parts, entitled Strata, is temporal and open-ended, with new beaded works added as the exhibition travels while also being dependent upon the interaction of gallery visitors. The recorded sounds of beads being dropped into a mason jar adds to our experience of her work, embodying the physical accumulation of bands of colour that are reminiscent of deposits of silt, sand, lava and coal.

These beaded reckonings of action across time – one bead carefully aligned with the next to form row upon row of striations of colour – were interpreted as musical scores by UBC School of Music students, each creating works specifically for the carillon, the chiming mechanism of the Ladner Clock Tower.

In the following texts, Sasha Kow, Athena Loredo and Joseph Stacy share their individual approaches to composing for the carillon. In response to these performances, the Belkin’s Academic Programs Assistants Megan Jenkins and Marcus Prasad offer their experiences of actively listening across space. These texts consider the history of the carillon being used as an assertion of colonial order and its role within the institutional setting of UBC, while reflecting upon the intricacies of labour inspired by Whetung’s beaded works as an alternate marker of time in public space.

Photos: Rachel Topham Photography

Video: Aya Garcia

Audio Recordings: Marcus Prasad and Sasha Kow

Sasha Kow

“How can a score be a tool for decolonization?” was a question posed by curators Dylan Robinson and Candice Hopkins, to the artists for Soundings. In crafting my response to Whetung’s work which was also a response to the question, I wanted to explore ideas of temporality, as well as ideas around freedom and control.

“How can a score be a tool for decolonization?” was a question posed by curators Dylan Robinson and Candice Hopkins, to the artists for Soundings. In crafting my response to Whetung’s work which was also a response to the question, I wanted to explore ideas of temporality, as well as ideas around freedom and control.

The sounds created during this performance were meant to evoke Whetung’s beading process, both conceptually and physically. During a phone interview with Whetung, she explained that her motivation for this piece was to give up control within her work to the audience. Instead of having complete control over what beads were used, the work calls for an active response from the viewer. Whetung mentioned the freedom that came with giving up that control.

In addition to juxtaposing these two ideas, I felt a need to focus on the physical aspects of Whetung’s beading process. I wanted to represent the collapse in temporality through thinking about sounds that would happen before and after the beaded work was completed. I thought a lot about what sounds were made by the beads. I imagined the sounds that happened as the beads were poured into the jar, scooped out of the jar, and as they hit the surface. Each of these produced a specific sound, sometimes a trickling sound, sometimes a wash of sound, sometimes loud, and sometimes soft. Whetung’s beadwork also made me reflect on the importance of beading in my own culture, the Peranakan culture. Beading was means for my people to reconcile the different cultures that were adopted through immigration and colonization. In line with my approach to Whetung’s process, I couldn’t help but wonder about the sounds that happened as my ancestors beaded. Were they singing? Was there a call for prayer as they beaded? What did the environment sound like?

Being given the opportunity to respond to Whetung’s beadwork created space for me to challenge the idea of sound and temporality within sound. I am grateful for the work and support here at UBC in creating a safe space for these questions to be explored.

Athena Loredo

The word Strata comes from Latin, meaning layers. In composing this work, I considered the role of layers in Olivia Whetung’s work and how layers would inform mine. In the piece I wrote, I focused on elements of the music and score that I control and those in the players’ control. I composed the carillon part note by note, but the brass ensemble has more freedom. I sometimes give them melodies to play, but they also have moments to choose what to play. At times, the players can play any tune based on a set of notes or choose a note to play from a chord cluster. In this way, I set the boundaries and provide structure, and the players decide on the colour of the work through their choice of notes. In this sense, I wanted the process of my piece to reflect the process behind Strata.

The word Strata comes from Latin, meaning layers. In composing this work, I considered the role of layers in Olivia Whetung’s work and how layers would inform mine. In the piece I wrote, I focused on elements of the music and score that I control and those in the players’ control. I composed the carillon part note by note, but the brass ensemble has more freedom. I sometimes give them melodies to play, but they also have moments to choose what to play. At times, the players can play any tune based on a set of notes or choose a note to play from a chord cluster. In this way, I set the boundaries and provide structure, and the players decide on the colour of the work through their choice of notes. In this sense, I wanted the process of my piece to reflect the process behind Strata.

The word Strata comes from Latin, meaning layers. In composing this work, I considered the role of layers in Olivia Whetung’s work and how layers would inform mine. In the piece I wrote, I focused on elements of the music and score that I control and those in the players’ control. I composed the carillon part note by note, but the brass ensemble has more freedom. I sometimes give them melodies to play, but they also have moments to choose what to play. At times, the players can play any tune based on a set of notes or choose a note to play from a chord cluster. In this way, I set the boundaries and provide structure, and the players decide on the colour of the work through their choice of notes. In this sense, I wanted the process of my piece to reflect the process behind Strata. Musically, I also wanted to present the physical elements of Olivia Whetung’s Strata using sound. The slow-changing harmonies are meant to represent the colour blocks that the beading creates. Fugue subjects from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier are presented out of their tonal context to symbolize the beads themselves. The opening Cs are to represent the six loops that hold Strata to the nail in the wall. In the piece, temporal layers coexist simultaneously: the carillon plays in metered time while the ensemble alternates between metered and unmetered time. The carillon part is fixed and ends with a double bar line, but the players continue to play after the carillon is done playing. They get the final say musically, and their ending is not fixed — the players hold a note until they run out of breath. In writing Strata Tempora, I considered how conventional music notation shapes my perception of time and place.

The word Strata comes from Latin, meaning layers. In composing this work, I considered the role of layers in Olivia Whetung’s work and how layers would inform mine. In the piece I wrote, I focused on elements of the music and score that I control and those in the players’ control. I composed the carillon part note by note, but the brass ensemble has more freedom. I sometimes give them melodies to play, but they also have moments to choose what to play. At times, the players can play any tune based on a set of notes or choose a note to play from a chord cluster. In this way, I set the boundaries and provide structure, and the players decide on the colour of the work through their choice of notes. In this sense, I wanted the process of my piece to reflect the process behind Strata. Musically, I also wanted to present the physical elements of Olivia Whetung’s Strata using sound. The slow-changing harmonies are meant to represent the colour blocks that the beading creates. Fugue subjects from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier are presented out of their tonal context to symbolize the beads themselves. The opening Cs are to represent the six loops that hold Strata to the nail in the wall. In the piece, temporal layers coexist simultaneously: the carillon plays in metered time while the ensemble alternates between metered and unmetered time. The carillon part is fixed and ends with a double bar line, but the players continue to play after the carillon is done playing. They get the final say musically, and their ending is not fixed — the players hold a note until they run out of breath. In writing Strata Tempora, I considered how conventional music notation shapes my perception of time and place.

I am grateful for the support of my peers and professors at UBC. I appreciated this opportunity to learn more about decolonization and art music and to contextualize my thoughts in the way I know best: through music.

Performance of a composition for carillon and brass by Athena Loredo

7 minutes, 58 seconds

Download the original score (PDF) 451 KB

Joseph Stacy

Whetung’s work involves so much connectivity; connection between thousands of beads, the viewer pouring those beads into the jar, the artist weaving layers of beads into this loom, and then me as the performer getting to interpret this artwork as sound. With that in mind, I felt inspired to connect with the space where I would perform, engaging with the surrounding acoustics, including the birdsong, fountain waters, and breezes, all of which seemed more apparent considering the sparse human activity on campus resulting from the pandemic.

Whetung’s work involves so much connectivity; connection between thousands of beads, the viewer pouring those beads into the jar, the artist weaving layers of beads into this loom, and then me as the performer getting to interpret this artwork as sound. With that in mind, I felt inspired to connect with the space where I would perform, engaging with the surrounding acoustics, including the birdsong, fountain waters, and breezes, all of which seemed more apparent considering the sparse human activity on campus resulting from the pandemic.

In realizing this score, I made a list of different aspects I wanted to be conscious of—pitch, rhythm, texture, timbre—and reflected on how those could be utilized to represent the artwork’s colours, mood, and affect. I also considered the work’s presentation in the gallery – the large nails mounted on the wall, the loops around those nails, and the audio stimulus of hearing the beads being poured into the jar. I also noticed in the display that the beads stopped at a certain length, but the threads almost reached the floor, which communicated a sense of continuity, an implication that the work was not stagnant, but ongoing. This statement on temporality is really at the heart of the underlying question of the Soundings exhibition: how can a score be a tool and call for decolonization? Having the opportunity to perform this piece outside the concert hall setting without a traditional Western score allowed for an unhindered sense of creative expression. The carillon has historically imposed colonial time on what is now known as North America, and the Eurocentric practice of art in academia can also be very restrictive. I hope these performances along with the others presented in the Soundings exhibition challenge that colonial narrative regarding time, artistry, and relationships to our surrounding world.

Affective Disruptions: Embodiment and the Leon Ladner Clock Tower

Megan Jenkins and Marcus Prasad

A series of performances by students at the UBC School of Music have interpreted and activated Olivia Whetung’s Strata, playing her beadworks as scores themselves. Shifting our understanding of Whetung’s pixelated composition to a digital score or as a kind of computer card, Sasha Kow, Athena Loredo, and Joseph Stacy “played” these works through the Ladner Clock Tower’s carillon bells. An engagement with the work as such investigated and revealed how, per Candice Hopkins’s and Dylan Robinson’s curatorial statement, a score can be a call and tool for decolonization. Centrally, this question prompts us to challenge scripts of knowledge transmission that are often taken as absolute, and to think about the resonances that intermedial and interdisciplinary engagement can foster.

A series of performances by students at the UBC School of Music have interpreted and activated Olivia Whetung’s Strata, playing her beadworks as scores themselves. Shifting our understanding of Whetung’s pixelated composition to a digital score or as a kind of computer card, Sasha Kow, Athena Loredo, and Joseph Stacy “played” these works through the Ladner Clock Tower’s carillon bells. An engagement with the work as such investigated and revealed how, per Candice Hopkins’s and Dylan Robinson’s curatorial statement, a score can be a call and tool for decolonization. Centrally, this question prompts us to challenge scripts of knowledge transmission that are often taken as absolute, and to think about the resonances that intermedial and interdisciplinary engagement can foster. Joseph Stacy, a graduate student at UBC’s School of Music, conducted his performance on a windy afternoon in late October. As part of our research, we decided to record the sounds emanating from the Clock Tower as they interacted with the everyday noises on UBC campus, preserving the echoes and reverb digitally. Sounds that were uncontrolled, unexpected, and often messy found their way into our audio file, allowing us to draw some thought-provoking conclusions from the carillon performances as a whole.

The carillon and Ladner Clock Tower are two components of UBC campus that we had often taken for granted as students at UBC. At the time of Joseph’s performance, we’re three months into a new year here as interns at the Belkin working with the Soundings exhibition, and we’ve found that our relationships to these sites are now thrown into suspension. Our interactions and movements across campus are no longer structured by lectures, seminars, and study groups, with deadlines, anxiety, and stacks of scribbled notes—instead, we are reoriented toward new projects with different goals that reshape the entirety of our engagements with the institution and its monuments. A perfectly consistent sonic notation indicating the top of the hour, the steady cadence of the Clock Tower have reverberated unrelentingly throughout our time here. Though before, those chimes never meant more than a signal of time passing, a transition from minute 59 back to minute 00, fading into the background of an often noisy campus.

All the while though, this cyclical marking of time played an integral role in the formation of a spatial rhythm of the everyday—an unconscious tempo that stratified time and existence on campus into a kind of habitus. We create routines in this space. Running from class to class, grabbing a coffee on our walk to the library, or meeting up with friends to sit in the grass, we unknowingly fit these experiences into an orientation of the banal, the everyday, and the normal. Pierre Bourdieu argues that the habitus is like a systemic qualification of this sense of normativity, constituted by transposable dispositions like these kinds of activities. It is reinforced by continuous action, and this continuity becomes a rule that is to be enforced. The Clock Tower, then, striking every hour on the hour while these practices that constitute a sense of normativity take place, acts as a sonic constituent within this spatial and temporal formation. An aural intervention that remains unseen and relatively unnoticed, its consistent hourly marking as such substantiates and perpetuates our lived experience of the everyday.

But what happens when this consistency, regularity, and certainty is disrupted?

We find this question to be one that opens up to an array of critical possibilities. Especially Marcus, who just completed an MA thesis on how horror movies represent normative spaces and disrupt them to evoke fear. In many ways, the performances of Strata find resonance with this kind of affective disruption—not so much to evoke fear, but rather to incite a thoughtful reconsideration of space and its contribution to a common experience on UBC campus. It is perhaps alarming to be confronted with such a change at first. Surely, the chimes of the Clock Tower go unnoticed by most, especially to those that spend most of their days on campus. When awareness is directed to them however, through a reconfiguration of the chimes into musical expressions that contrast the usual one-note bong for a small moment in time, we experience an affective reaction. Something within the sensory landscape of normativity has shifted.

***

Stacy’s performance of Strata began at around 3:15pm. He disappeared behind the sliding glass doors of a small cement room that appeared to emerge from the ground, and sat at the decades-old wooden carillon. As he pressed its keys, the bells began to clang in accordance—not the expected bongs from the top of the hour, but rather improvised trills, staccatos, and arpeggios echoing from the peak of the towering structure.

We walked around campus throughout the length of his performance, which lasted 17 or so minutes, noting how the sounds travelled amongst trees, brushed up against buildings, and intertwined themselves with the conversations of passersby. Often the sound of the bells were overtaken by construction projects, or by cars driving by near the Rose Garden. In some special moments however, we would hit a sweet spot, where the apex of the tower would peek through an opening in the trees, and the bells would reverberate around the open space of Main Mall.

Each note resonated differently as we meandered around campus, and this was reflected in the reactions from strangers we passed during our ambulation. Most did not notice any change until reaching the flat plaza in front of Koerner Library, where the sounds most clearly echoed. Some stopped to record with the phones while others chatted about it to their friends with furrowed brows, continuing on with their walks. We wonder about this sense of confusion or fascination, and what it is that evokes this kind of affect. Is it the fact that some kind of music is being played loudly in a public space, or is it the fact that it comes from the Ladner Clock Tower, a monument that normally emits one steady and unchanged sound?

Each note resonated differently as we meandered around campus, and this was reflected in the reactions from strangers we passed during our ambulation. Most did not notice any change until reaching the flat plaza in front of Koerner Library, where the sounds most clearly echoed. Some stopped to record with the phones while others chatted about it to their friends with furrowed brows, continuing on with their walks. We wonder about this sense of confusion or fascination, and what it is that evokes this kind of affect. Is it the fact that some kind of music is being played loudly in a public space, or is it the fact that it comes from the Ladner Clock Tower, a monument that normally emits one steady and unchanged sound?

We are brought to the seemingly unrevolutionary conclusion that yes, people were confused and/or fascinated by the performance because it was abnormal and unexpected. What is more intriguing however, is what this reaction of pause and questioning can ultimately speak to, as well as the spatial and sonic awareness it can invite. The Clock Tower’s hourly chimes play a role in the formation of a normative structure of activity, socialization, and subjectivity, but this systematic operation has been altered by Stacy’s performance of Strata. The carillon has been activated in a different way, interpreting each bead as a musical notation to echo new, unstructured, and contingent sounds across the space of campus. In turn, the rigid and sterile quality of the Clock Tower’s original routine is repurposed, now becoming an invitational intervention into the sonic landscape of the everyday.

Reinscribing sonic space as such is uniquely subversive. As we conduct our everyday activities, creating the unconscious formulas that constitute quotidian existence on campus, this performance instructs us to pause and reflect. We are asked to reconsider what is subsumed into the mechanics of the everyday, to pick up what falls into the background of our busy lives and goes unnoticed. The chimes of the Clock Tower, now brought to the fore in our conscious awareness, encourage us to reframe other constituents of the everyday we have taken for granted. The result of this mindful attention is the creation of a new space, somewhat superimposed onto the previous—one that includes a more critical perspective on sound, space, and place.

Reinscribing sonic space as such is uniquely subversive. As we conduct our everyday activities, creating the unconscious formulas that constitute quotidian existence on campus, this performance instructs us to pause and reflect. We are asked to reconsider what is subsumed into the mechanics of the everyday, to pick up what falls into the background of our busy lives and goes unnoticed. The chimes of the Clock Tower, now brought to the fore in our conscious awareness, encourage us to reframe other constituents of the everyday we have taken for granted. The result of this mindful attention is the creation of a new space, somewhat superimposed onto the previous—one that includes a more critical perspective on sound, space, and place.

Bringing awareness to the constituents of subjectivity and how they are filtered through the sonic, the visual, and the haptic, links back to the aims of Soundings as a whole. As uninvited guests on Musqueam territory, what is at stake when we create and uphold a normative experience? How does reinscribing sound into a space speak to other reinscriptions that have taken place on unceded territory? Now that we have paused and reflected on our own everyday routines, cycles, and systems, how can we mobilize our awareness toward tangible, equitable action?

The carillon performances, in bringing attention to such constituents, necessarily implicate the fact of the land on which we reside. The University of British Columbia, and all “Western” Universities and bodies like them, are colonial, oppressive structures. The lands upon which UBC Vancouver sprawls belong to the Musqueam First Nation, and we settlers are here—with our clock towers, with our bullshit, with our minds toward ownership—as uninvited and disastrously imposing guests. So ours are structures which physically demarcate space and land that does not belong to us with buildings, malls, and clock towers; every day, we fill those buildings with knowledges, pedagogies, and practices which were not native to these lands.

It would be remiss of us to not discuss the location of the Ladner Clock Tower, and the tower’s provenance. Erected following a dedicated charitable donation by Leon Ladner in 1966, the clock tower for decades has and continues to cast a long, phallic shadow across the UBC campus. Ladner, a descendent of “pioneers,” was born and raised in a town named for his family (now a suburb home to approximately 20,000 people near Langley, BC). As an adult, he was a lawyer, an MP, and a philanthropist; when he made a donation to build the clock tower, he intended it as a monument to the founding pioneers of British Columbia—especially his father and grandfather. He was a long time supporter of the university, and as such, hoped his clock tower would inspire the students of UBC for decades to come. He said:

“When that clock tower is completed and the clock rings out the passing of each hour, I hope it will remind the young students that not only does time go fast, but that the hours at our university are very precious and the use of those hours will seriously affect the success, the happiness and the future of their lives.”

“When that clock tower is completed and the clock rings out the passing of each hour, I hope it will remind the young students that not only does time go fast, but that the hours at our university are very precious and the use of those hours will seriously affect the success, the happiness and the future of their lives.”

Ladner, it seems, always intended the clock tower as an undergirding constant designed to give structure to the lives of students. Over decades, it has rung out every hour, and its consistency has paradoxically removed it to near invisibility in some ways. Like breathing, or like our own heartbeats, the tower rings out, but after enough time spent on the campus, we cease to register its presence. It is stitched through our fabric of daily existence on campus—a mechanism of familiarity which, theoretically, we can also take as metonymic of the presence of the university. After all these years, the institution’s existence on these lands could feel almost natural; in reality, our existence here is anything but.

To wit, the repetition of this normative sonic cue was meant to usurp other realities and schedules in favour of its own. The clock tower is a fixed, constant structure that replicates settler ideologies that resonate across campus (toward “success,” happiness, and futures, ominously). We needn’t look further than 100 metres away from the foot of the clock tower to see this colonial pressure in action.

Across the beautifully manicured, grassy amphitheatre at the foot of the clock tower rests the Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre (IRSHDC). The centre includes a living archive and collection of documentation intended to address “the colonial legacy of residential schools and other policies imposed by the Canadian government on Indigenous Peoples, and ensures that this history is acknowledged, examined and understood within the UBC community.” The centre also supports teaching and other cross disciplinary initiatives intended to facilitate dialogues along with access to records pertaining to the legacy of Canada’s residential school system; this work extends to records and research support for families grappling with their own history within residential school systems. The juxtaposition of these two structures, the IRSHDC and the Ladner Clock Tower, creates a tense relationality not only in their presence but in the continuous effacement of these unceded lands in the chiming of the bell.

On a recent tour with the Belkin’s Naomi Sawada, we walked to the plaza and looked down over the IRSHDC and the amphitheater, dwarfed by the towering clock. In reference to an essay by Patrick Nickleson (which in turn cites works by one of Soundings’ curators, Dylan Robinson) Sawada discussed the oddity of this juxtaposition, especially in considering the bell’s chime every hour and the resonance clocks and their carillon bells have as violent, didactic tools in residential schools. Nickleson offers the accounts of several residential school survivors discussing the prevalence of bells and clocks as colonial tools of order and discipline, and writes, “there are lastly innumerable actual Natives, people actually indigenous to this land for whom bells were one more element in a newly colonized soundscape of violence, oppression, loss, trauma, and genocide.” In service of further illustration, a quote regarding the Methodist Mount Elgin Residential School in Ontario is offered here, penned by 1851 principal Samuel Rose:

“Regulations. – The bell rings at 5 A.M. when the children rise, wash, dress and are made ready for breakfast. At half-past-five they breakfast; after which they all assemble in the large school-room and unite in reading the Scriptures, singing and prayer. . . At one, they enter School, where they are taught till half-past three, after which they resume their manual employment till six. At six they sup and again unite in reading the Scriptures, singing and prayer. . . . They are never left alone, but are constantly under the eye of some of those engaged in this arduous work.”

Rose, in a similar manner to Ladner (though very different circumstances, obviously) knew how powerful the bell could be in controlling his pupils. Ladner sought to control university students (and was angry when they spoke out against the clock tower). Rose sought to violently regulate the lives Indigenous children toward genocidal ends.

Further, Dorothy Day, a survivor of Mount Elgin who was kept at the school from 1929 to 1930, said:

“You had five minutes to get up when the first bell would ring, five minutes to get up and put your clothes on, five minutes to run two flights of stairs and be downstairs and stand in line for the second bell to go in and wash your hands and face. And that’s all they give you—five minutes to wash your hands and face and brush your teeth, and comb your hair and stand in line again. We’d be running over each other to get down those stairs—it was good exercise—no wonder nobody ever put on weight. They’d be standing at the bottom of the stairs with a watch to make sure you were down there in 5 minutes. You should see the girls coming down there—we had those boots that laced up high and they’d tie them together and lace them when they got to the bottom. If you weren’t down there—up you would go to get the strap. They would give you the strap for being late—you were supposed to be down there when you were supposed to be.”

The bell was a ruthless, pervasive sonic agent of order cast down from the merciless powers that be; if one did not obey the bell—which was never late, and never wavered—one was punished. The bell rang five minutes ago, and you are not where you’re meant to be. You did not obey the bell. You will be punished, so when the bell rings next time, you listen.

The bell ordered the bodies and lives of Indigenous children, and with its normative function, created a justification for punishment and violence; all the while its invisible but encompassing nature made it seem untouchable, inarguable.

The Ladner Clock Tower is so transparently a tool of colonialism that its position across the amphitheatre from the IRSHDC is doubly imposing, almost threatening. The bell, an archetypal tool of order and punishment in the church-run residential school system, still rings out, hour by hour, over the IRSHDC, over the Musqueam land.

The Ladner Clock Tower is so transparently a tool of colonialism that its position across the amphitheatre from the IRSHDC is doubly imposing, almost threatening. The bell, an archetypal tool of order and punishment in the church-run residential school system, still rings out, hour by hour, over the IRSHDC, over the Musqueam land.

In this context, we can consider the nuances of these carillon performances as they disrupted—ruptured, even—and invited a reconstitution of space on the university campus. The performance, in the context of the Clock’s history and its proximity to the IRSHDC, momentarily also scrubbed the normative forces of the Clock by performing the score of an Indigenous woman, Whetung, rather than the score of colonialism (though the Tower itself was tangibly unchanged).

While Joseph Stacy performed his response to Strata, and with all of this in mind, we opted to take an intentional ambulation around the Clock Tower during the performance to consider the role of location and movement, and of bodies in space, of positionality and specificity. One of us began our ambulation by walking from the Clock Tower to the northernmost flagpole on campus, looking out toward the land and waters, while the other took a static position, capturing the echoes and resonances of the performance from a fixed position. Through this exercise, we were able to enact and contextualize the abiding force of our own subjectivity on these lands: depending on our perspective, Stacy’s performance of Whetung’s work morphed; sometimes tangling with crows overhead, other times limping across brutalist courtyards. At base, our experiences of Strata’s resonances were different depending on our positionality, and this fact can be extended to conceptualize the nature of being. This is a theme we see underscoring Soundings: knowledge is a cumulative assemblage shaped unavoidably by our own contingencies, but every knowledge—read every perspective—is precious. The Clock Tower and its chimes function to contradict and tamp down the practical matters of this proposition.

That these perspectives undermined the capitalist, apathetic rigidity created and perpetuated by Leon Ladner’s investment—a Clock Tower that he named after himself, which, if we may be colloquial, totally sends us—demonstrates how such ways of knowing and being expand far outside Western ontologies. Thinking of the many ways to be and to know, not from hours carefully spent at university but from cultivating an embodied sense of presence, like so many dots in a matrix, draws out Strata as an act of protest, seeking an intervention in “progress” and its accoutrements, and agency restored to our bodies in space.

Works Cited

Pierre Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice. Translated by Richard Nice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1972).

Patrick Nickelson, “The Message of the Carillon: Bells as Instruments of Colonialism in Twentieth-Century Canada,” Intersections 36:2 (October 1, 2018): 13–25, https://doi.org/10.7202/1051594ar.

Rev. Rose Report, 1851, in Elizabeth Graham, ed., The Mush Hole: Life at Two Indian Residential Schools (Ontario: Heffle Publishing, 1997), 227–28.

Erwin Wodarczak, “The Clock Tower and the Anarchists,” UBC Trek Magazine, November 27, 2013, https://trekmagazine.alumni.ubc.ca/2013/dec-2013/features/the-clock-tower-and-the-anarchists/.

UBC Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre, “What We Do,” https://irshdc.ubc.ca/about/what-we-do/.

Joseph Stacy – Carillon – October 21 (Recording 1)

Joseph Stacy – Carillon – October 21 (Recording 2)

Joseph Stacy – Carillon – October 28

Sasha Kow – Carillon – December 2

Sasha Kow – Carillon – December 6

-

Sasha Kow

MusicianSasha Kow is a Malaysian composer based in Vancouver. She completed her BMus in Composition at the University of Oregon, and is currently in her second year of her Master of Music in Music Composition at the University of British Columbia. Her work strives to understand where and how her background and upbringing fit into the world of Western contemporary art music. Through her involvement with the Score Cluster Research, she seeks to diversify her approach to writing music and hearing sound.

Read More

-

Athena Loredo

Musician and ComposerAthena Loredo is a composer based in Vancouver. She grew up in Newfoundland and obtained a BMus (Hons) in composition from Memorial University. Currently, Loredo is completing a Master’s in Composition at the University of British Columbia. Her compositional style is influenced by the manipulation of musical fragments. From quoting Bach, Prokofiev and Dvorak in a symphonic poem to creating variations on a Mexican folk song, Loredo explores combinations of timbres and melodic fragments, reworking music to create something new.

Read More

-

Joseph Stacy

MusicianJoseph Stacy is from the United States, having grown up in the Appalachian community of Pulaski, Virginia. He graduated summa cum laude from Ohio University in 2019 with a BMus in Piano Performance and Pedagogy. He is currently in his second year of the Master of Music in Piano Performance at the University of British Columbia, where he is a student of Mark Anderson. In addition to his performance career, Stacy has presented at multiple state and national conferences throughout the US on subjects ranging from performance health to equitable access of music involvement. Stacy seeks social justice engagement through his work as a performer, pedagogue and scholar by pursuing interdisciplinary projects that are culturally relevant and dismantle colonialist norms persisting throughout North American society.

Read More

-

Olivia Whetung

ArtistOlivia Whetung is anishinaabekwe and a member of Curve Lake First Nation. She completed her BFA with a minor in anishinaabemowin at Algoma University in 2013, and her MFA at the University of British Columbia in 2016. Whetung works in various media including beadwork, printmaking, and digital media. Her work explores acts of/active native presence, as well as the challenges of working with/in/through Indigenous languages in an art world dominated by the English language. Her work is informed in part by her experiences as an anishinaabemowin learner. Whetung is from the area now called the Kawarthas, and presently resides on Chemong Lake.

Read More

Related

-

Exhibition

8 Sep – 6 Dec 2020

Soundings: An Exhibition in Five Parts

Soundings: An Exhibition in Five Parts features newly commissioned scores, performances, videos, sculptures and sound by Indigenous and other artists who respond to the question, How can a score be a call and tool for decolonization? Unfolding in a sequence of five parts, the scores take the form of beadwork, videos, objects, graphic notation, historical belongings and written instructions. During the exhibition, these scores are activated at specific moments by musicians, dancers, performers and members of the public, gradually filling the gallery and surrounding public spaces with sound and action. Curated by Candice Hopkins and Dylan Robinson, Soundings is cumulative, limning an ever-changing community of artworks, shared experience and engagement. Shifting and evolving, it gains new artists and players in each location. For this iteration on Musqueam territory, the Belkin has collaborated with UBC's Musqueam Language Program in partnership with the Musqueam Indian Band Language and Culture Department; School of Music; Chan Centre for Performing Arts; First Nations House of Learning and Museum of Anthropology to support the production of new artworks and performances by local artists.

[more] -

Event

Wednesday 21 Oct 2020 at 3 pm

Wednesday 28 Oct 2020 at 3 pm

Wednesday 25 Nov 2020 at 2 pm

Wednesday 2 Dec 2020 at 3 pm

Sunday 6 Dec 2020 at 3 pm

Soundings: Olivia Whetung and the Ladner Clock Tower Carillon

Whetung invites gallery visitors to pour different coloured beads from individual small jars into one large vessel, creating a layering of sounds as each bead joins the growing pile. Once the container is filled, the artist turns the amalgam of beads into an entirely new piece – a rectangular beadwork unique to the Belkin’s iteration of the exhibition.

[more] -

Event

Sunday 8 Nov 2020 at 3 pm

Soundings: Camille Georgeson-Usher and Rachel Kiyo Iwaasa

through, in between oceans part 2 by Camille Georgeson-Usher is a beaded installation, completed during the isolation of the Spring 2020 pandemic. The artist worked from home in Toronto, a departure from her intention to spend several months on Galiano Island, BC, where she was raised.

[more] -

Event

10 Sep 2020

Soundings: Diamond Point and Coastal Wolf Pack

Forming two continuous lines on this part of the traditional, ancestral and unceded territory of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) people, wəɬ m̓i ct q̓pəθət tə ɬniməɬ by Diamond Point presents two images repeating in a sequence hung on the lampposts along UBC’s Main Mall from James Hart’s Reconciliation Pole to the plaza just beyond the Belkin.

[more] -

Event

Soundings: Germaine Koh

Germaine Koh’s drum is made from one of the cedar tree stumps she first brought to site for use as physical distancing stations. She worked with Belkin staff during Summer 2020 to develop COVID-19 safety and visitor interaction protocols that recognized the importance of collective care and teamwork.

[more] -

Event

8 Sep 2020

Soundings: Greg Staats

[more]

[more] -

Event

8 Sep 2020

Soundings: Peter Morin and Parmela Attariwala

In Part One of NDN Love Songs, Peter Morin offers a score of instructions to musicians presented alongside seven video portraits. Part Two presents videos of recordings of previous iterations of the Soundings exhibition at Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Gund Gallery and Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery. In Part Three, Parmela Attariwala performs the score on the violin at the Belkin.

[more] -

Event

8 Oct 2020 at 4 pm

Soundings: Raven Chacon and Symphonic Wind Ensemble

Around the corner from the Belkin Gallery, Raven Chacon's score American Ledger (No. 1) hangs on the exterior of the Music Building at 6361 Memorial Road, UBC. The score incorporates a traditional musical score with Navajo iconography and is to be performed by "many players with sustaining and percussive instruments, voices, coins, axe and wood, a police whistle and the striking of a match."

[more] -

Event

Monday 30 Nov 2020 at 4:30 pm

Soundings: Tania Willard and Melody Courage

Surrounded/Surrounding includes a wood-burning fire bowl, etched leather camp stools and a life-sized rendering of the artist’s wood pile in a graphic score. Written on the split logs and the spaces between them are references to the breathing, beating labour that creates what a fire needs, as well as the trees, sun, sky and ground that surrounds and creates all else.

[more] -

Event

Dec 2020

Soundings: UBC Contemporary Players Respond

In lieu of a public concert at the Belkin as has occurred in recent years, musicians from UBC Contemporary Players chose a work by a Canadian composer to perform in an empty gallery, responding to the works of Soundings: An Exhibition in Five Parts. Videos of these performances are shared here for reference, research, and enjoyment in perpetuity. Soundings asks how a score can be a call and a tool for decolonization. The exhibition's corresponding investigations take at their centre questions of embodiment and subjectivity, of calls and responses. What are the practical matters of embodied decolonization, and how can we practice them? How does embodiment facilitate unlearning, unknowing, and the visioning of Indigenous ontologies?

[more] -

News

10 Dec 2020

Soundings: Marking Time

[more]

[more] -

News

31 Aug 2020

Soundings: Reading Room

The following is a list of resources related to Soundings: An Exhibition in Five Parts. The list of resources compiled here is not an official recommendation, but is rather a list of suggested readings compiled by Public Programs and graduate student researchers at the Belkin Art Gallery. These readings are intended to provide additional context for the exhibition and act as springboards for further research or questions stemming from the exhibition, artists, and works involved.

[more] -

News

30 Nov 2020

Belkin x CRWR: Soundings

In response to Soundings: An Exhibition in Five Parts, a group of Creative Writing graduate students at the University of British Columbia have made a series of activities for visitors to take part in during their visits to the gallery. Thinking through the idea of a score as a call to respond, these activities range from sound walks to reflective worksheets to small group workshops.

[more]