16 Jun 2020

Sonic Responses

A facet of campus life that has changed significantly with the pandemic is one that most of us never noticed before but would be struck by now: the sounds of campus. The whir of students moving between classes, the hum of vehicles on the road and the ripples of classroom discussion were all familiar noises, so much so that we grew inured to them. But they are gone now. In their place, a hush has emerged. The stillness is at once eerie, peaceful and captivating. It calls out to be pondered and explored. Sonic Responses answers that call. As heard in the works of R. Murray Schafer, Hildegard Westerkamp and Barry Truax, sound offers a way of entering a soundscape and hearing in new ways the sounds encountered there. So it is with the quiet soundscape that has emerged on campus. The responses in this project take the form of performers playing in campus locations claimed by silence and composers transforming sounds recorded across UBC. Their music-making confronts and enters into a dialogue with the quiet that now resides on campus.

Sonic Responses strengthens the collaborations between the Belkin and the School of Music. The project is led by Barbara Cole, Curator of Outdoor Art, David Metzer, Professor of Musicology and Chair of the University Art Committee, and Judith Valerie Engel, a doctoral candidate in piano performance. Faculty and student performers from the School of Music explore the campus soundscape. The repertoire for Sonic Responses stretches across a broad range of traditions. Videos of performances and compositions will be included here as the project moves along. The following essays by Cole, Metzer and Engel consider the project through each individual’s experience of location, sound, music and performance, offering different perspectives of the performances.

Silence by David Metzer

I have studied silence, particularly how it functions in musical works. I never thought, though, that I would study how it functions in the place where I study: the UBC campus. Campus is now quiet. A new soundscape has emerged, one that my colleagues Judith Valerie, Barbara and I have set out to explore along with musicians and composers from the School of Music.

I have studied silence, particularly how it functions in musical works. I never thought, though, that I would study how it functions in the place where I study: the UBC campus. Campus is now quiet. A new soundscape has emerged, one that my colleagues Judith Valerie, Barbara and I have set out to explore along with musicians and composers from the School of Music.

The closure of campus has created an unusual context for silence. Quiet was abruptly imposed. Classroom voices, the bustle between classes and the noises of work stopped, leaving behind an emptiness. The suddenness of this quiet ties into a perception of silence as loss. It is the void created by the absence of noise. The pandemic has brought about loss. There have been dire losses of life, health and employment. Then there are those of the familiar aspects of life, so familiar that we do not notice them until they are gone. Such is the case with the sounds on campus. Music is not pouring out of the School of Music. Laughter is not crackling here and there. Quiet rules, and with it, another layer of loss emerges.

I was uneasy to return to campus largely because of the feelings of loss that I would encounter there. Many people said that the quiet would be eerie. That actually intrigued me. I like when weird gets tense. It was the emptiness that put me off. Not just the absence of the sounds that I would normally hear but also the sounds that I made there. I could raise my voice as I would in a lecture but who would hear it? Why even raise it? I have become part of the emptiness.

My studies of silence eased these anxieties. One of the things that I have learned about silence is that you can learn things from it. Silence teaches. From it, you realize that things are always changing, including quiet. It conveys emptiness, but it is never empty. John Cage also taught us this. He was, after all, an enlightened student of silence. Motes of sound will emerge here and there. Silence may hold for a while, but it will break. The sounds of life eventually intrude upon it. So it is with the UBC campus. Walking around, I have been struck by how much construction is underway. Or maybe I should not be surprised. Construction is one of the few industries that has continued on during the pandemic. The sounds of trucks and drilling have become the background noise of the time, even on the hushed campus.

Being on campus has reminded me that we should engage silence, not passively respond to it. The composers that I study interact with quiet. They situate pieces at the border between silence and sound. At this thin line, music disrupts stillness, and quiet seeps into music. There is a give and take between the two. The performances of pieces on campus in this project offer the opportunity to engage silence, to communicate with it, to learn from it. The performers can throw music into silence, and we can hear how it responds. And to turn things around, what does silence add to the pieces? For example, how does Joseph Eggleston’s performance of movements from Bach’s Cello Suites interact with and shape our perceptions of the quiet that it reaches out to? And how does silence enrich the pauses at the end of phrases or how does it assert itself after patiently waiting for the conclusion of the performance? The stillness of campus provides a new way of listening to “The Abyss of the Birds” movement from Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time. The movement sets the light of birdsong against the darkness of the abyss. With Carlos Savall Guardiola’s performance, we can hear the solo clarinet evoking birds against the quiet created by the pandemic. Is there an abyss on campus? Do the clarinet and the sound of actual birds turn us away from emptiness?

One of the ways that we perceive silence is as peacefulness, the flipside of eeriness. The idea of tranquility emerges from the connections made between silence and nature. We think that nature would be quiet if not for the noise of humans, which brings home how self-centred our views of nature and quiet are. To hear patches of quiet is to take us to that natural state. Far from shattering stillness, some of the performed pieces can root us in both it and nature, as happens in Nathania Ko’s performance of “Earth: Buddhist Music.” The resonant low notes provide deep earthly vibrations.

Quiet is ephemeral. It always passes. So too will its current reign on campus. The upcoming September will not be as hectic and noisy as usual, but there will still be commotion. When I am walking around campus this fall, I will have to think back to the stillness brought about by the dawn of the pandemic. That is how quickly distant these days will become. As part of Everything This Changes, Sonic Responses has offered an opportunity to document and partake in this unique moment in the history of the campus and shows us how much we have to learn from silence.

Pathways by Barbara Cole

I have walked around campus quite a bit over the last couple of years, scouting for possible locations for public art, going to and from meetings and sometimes partaking in guided walks, tree walks, sensorial walks, outdoor art walks and plain old take-a-break walks.

I have walked around campus quite a bit over the last couple of years, scouting for possible locations for public art, going to and from meetings and sometimes partaking in guided walks, tree walks, sensorial walks, outdoor art walks and plain old take-a-break walks. I have experienced the seasonal shifts in the landscape as well as the flow of people, the summers so remarkably calm compared to the surge of bodies that come with the start of each fall. Under the lens of the pandemic, descriptions of the halcyon days of those summers now seem greatly exaggerated – this new imposed quiet is an aggressive calm, eerily marked by unpopulated plazas, empty classrooms, locked doors and shuttered cafeterias and cafes.

Early in the lockdown, my ambulatory roaming became established as a necessary habit. I had broken my wrist in a bicycle accident and my daily “distraction” walks battled the boredom and pain. It was rewarding to simply self-propel through space with a heightened awareness of light, sound and growth. The campus, especially its edges with rainforest fringe, were among the places I sought. While the centre of the built campus slumbered, nature just carried on, trees grew, birds nested and the lines of desire paths began to self-seed and fill. My listening gradually became more active and embodied and I began to pay attention to UBC’s soundscape as being representative of a unique moment in its history. Now was the time to invite responses to this new (and probably fleeting) condition and to record it!

For me, a collaborative approach to working in public space is a preferred condition and Sonic Responses was conceived as a project that called out for synergetic exploration. The School of Music and the Belkin have a history of exchange that allowed us to mobilize quickly as a collaborative team. David, Judith Valerie and I weren’t and still aren’t entirely sure where the project is going to lead and that excites me. Our respective fields of study and interests can be seen as a merging of different ecologies of understandings.

The three of us began our collaboration by taking up walking as a tool for learning and sharing. We set off on a meandering course, stopping at different locations, comparing our observations and mapping them with a sensorial ear for how these seemingly quiescent spaces might become reactivated and resonate for listeners.

Our combined interests were in place, people and pieces – the site, the performers and the music they would play. For me, it was the locations that led. We purposefully chose a variety, in the hopes that cumulatively they would form a campus gestalt. Included are some of the more iconic viewpoints – the Ladner Clock Tower and Main Mall – some locations that speak to the landscape, others to the architecture and perhaps most compelling of all, the spots that are out of the way or hidden (“armpits” as we started to call them). We noted their physical characteristics, acoustic qualities and different ambient sounds and pictured what kinds of instruments would be able to hold their own in these particular outdoor situations. We paid attention to the visual cues that might exemplify this unique moment of time – the views to empty desks behind the windows, the waist-high grass, oblivious squirrels and long stretches of empty walkways.

David and Judith Valerie were insightful in their selection of performers and repertoire. For example, Carlos Savall Guardiola plays Olivier Messiaen “The Abyss of the Birds” for clarinet on Trail 7 that leads down to the south end of Wreck Beach – a piece drawn from the call and response of birds in nature played within the forest against the aural backdrop of distant running water, rustling leaves and maybe even the sounds of footsteps on planks as they approach and recede.

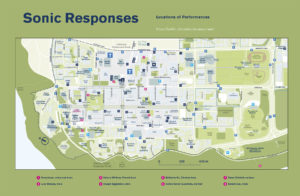

Judith Valerie is also developing a map or creative audit of the campus’ sonic spaces. Intended as a reference for future performances in UBC’s public spaces, it will serve both as a guide and an example of how other musicians have perceived and responded in the past. The spaces she intends to share represent the places of learning and reflection that happen between the buildings. The locations of the nine Sonic Responses will populate part of the map, and QR codes will lead listeners to the Belkin’s website, allowing for in-situ listening of the then absent performers. This act of conjuring will be amplified by Judith Valerie’s personal experience of campus, both as a student and as a resident.

This introductory text marks the beginning of our sonic walk during what could be described as a pregnant pause. We have and are experiencing something profound. Never has the moment been so ripe for change – climate change, systemic change and shifts in collective values that pose pressing decisions about which path to take. Do we retrace our route, take the loop trail or look at the terrain and come up with a new way of thinking about arrival?

Musicians by Judith Valerie Engel

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many people have experienced hardship and faced enormous challenges. I wish to focus on a particular group that is often overlooked these days: music students.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many people have experienced hardship and faced enormous challenges. I wish to focus on a particular group that is often overlooked these days: music students.

While they are students, musicians lead humble lives. Music is not a profession for those who want to make a lot of money right after graduation. The music student is accustomed to minimum-standards of life. Some of the foundations of that life may not be worth much in terms of dollars, but they are invaluable to musicians. The pandemic has threatened those foundations. One of them is the ability to find time and space to practice. Cut off from the instruments and practices rooms of a University School of Music, students have been struggling to find opportunities to practice. One thing we took for granted that is even more basic than practice is having colleagues around. Musicians, for the most part, are reliant on having someone to play with. Unless you are a pianist with a vast solo repertoire, you will be dependent on having a network of other musicians to join you in your rehearsal spaces and, eventually, on stage. The University, until recently, seemed like a secure safety net, guaranteeing that there would always be an abundance of musicians to choose from for your next collaborative project. Then came COVID-19.

As with universities around the globe, the UBC campus went quiet once the pandemic hit, leaving everyone to realize that “this is actually happening”. Where there used to be swarms of people running up and down the streets and students waiting in line for coffee, there was suddenly no one. The pandemic had swiftly removed all this liveliness. Instead of happy chatter echoing from every corner of the campus, there were barely any human sounds to be heard. Most of the students who had resided on campus decided to go home. Domestic students would re-join their families in other parts of the country and international students flew to their countries of origin. The campus was vacated by its human inhabitants. Soon the local wildlife got wind of this and parts of the land were reclaimed by families of Canadian geese and squirrels. Now and then a coyote would nonchalantly stroll through.

So what about the musicians? For the most part they went home, too – wherever that is. Some stayed on or near campus. What connected most of them, though is that they lost their collaborative partners. Suddenly, the solitude of the practice room (if musicians had access to a practice room) was all that was left. In a way, the campus and the musicians alike had lost their counterparts – the companions that helped create soundscapes brimming with noises and music.

This is how this project took on shape. A handful of performers and a composer were carefully selected to engage with the altered soundscape of the campus. The composer will “collect” sounds from all around the campus to explore the different auditory qualities that UBC has to offer these days. The sounds will provide material for an electroacoustic piece. The performers were paired up with locations with which to interact, creating a new kind of collaborative sound-creation. All the locations that were mapped out have distinct audio-atmospheric qualities, along with histories that have yet to be uncovered. The musicians will explore the locations through their performances. Health-care related safety standards still make it virtually impossible for anyone who does not live in a household of musicians to take up their usual rehearsal schedule. Thus, the solitude of the solo performance remains, although by placing it in a particular soundscape, it takes on an entirely new quality. We created a way for performers to respond to these altered circumstances in a meaningful artistic way.

Video recordings of the performances and compositions will be made available both on the Belkin Gallery website and on a virtual map online. They can also be accessed on the physical campus through QR codes installed in the locations of the performances. Through this mapping, we wish to bridge the divide between public and virtual space, allowing everyone who would want to visit the places of our recordings to be able to do so even if they cannot physically get to campus. We seek to claim the internet as a space for embodiment, providing the opportunity to retrace our steps and be engulfed by the soundscapes created for this sonic map.

And what about the musicians without whom none of this would be possible? Many of them find themselves removed from concert stages, without their colleagues, deprived of unlimited practice opportunities – and yet, they play.

Download a map of each Sonic Responses location. [PDF 3MB]

Images (above): Carlos Savall Guardiola at Trail 7, Wreck Beach; Biodiversity Research Centre, UBC; Earth Sciences Building courtyard, UBC; Nathania Ko at the Earth Sciences Building, UBC. Photos: Rachel Topham Photography

Related

-

Event

Sonic Responses: Carlos Savall Guardiola

Carlos Savall Guardiola on clarinet performing “Abîme des oiseaux / The Abyss of the Birds” by Olivier Messiaen as part of Sonic Responses, a collaboration between the UBC Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery and the School of Music. Performed on Trail 7 adjacent to the University of British Columbia, located on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territory of the Musqueam people.

[more] -

Event

Sonic Responses: Nathania Ko

Nathania Ko on Chinese harp performing “Earth,” the first piece of the cycle “Pao Xiu Luo Lan” by Xijiin Liu as part of Sonic Responses, a collaboration between the UBC Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery and the School of Music. Performed between the Centre for Interactive Research on Sustainability and the Pacific Museum of Earth at the University of British Columbia located on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territory of the Musqueam people.

[more] -

Event

Sonic Responses: Sempùlyan

Sempùlyan on drum singing a Musqueam paddle song as part of Sonic Responses, a collaboration between the UBC Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery and the School of Music. Performed in Library Garden (near Learner’s Walk) at the University of British Columbia, located on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territory of the Musqueam people.

[more] -

News

16 Jun 2020

Sonic Responses

A series of performances that explore the sounds - and silence - of a now-quiet campus.

[more] -

Event

Sonic Responses: Joseph Eggleston

Joseph Eggleston on cello as part of Sonic Responses, a collaboration between the UBC Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery and the School of Music. Performed behind the Beaty Biodiversity Research Centre just east of the Fairview Grove at the University of British Columbia located on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territory of the Musqueam people.

[more] -

Event

Sonic Responses: Lucy Strauss

Lucy Strauss plays viola on the knoll in front of the AMS Student Nest building at UBC.

[more] -

Event

Sonic Responses: Sodam Lee

Sodam Lee sings traditional Korean songs as part of Sonic Responses, a collaboration between the UBC Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery and the School of Music. Performed under a covered walkway between the Frederic Lassarre and School of Music buildings at the University of British Columbia located on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territory of the Musqueam people.

[more] -

Event

Sonic Responses: Taees Gheirati

Taees Gheirati on santour as part of Sonic Responses, a collaboration between the UBC Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery and the School of Music. Performed in the wooded area between the Asian Centre and Institute of Asian Research at the University of British Columbia located on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territory of the Musqueam people.

[more] -

Event

Sonic Responses: Valerie Whitney

Valerie Whitney on French horn performing “Idiom” by Elizabeth Raum as part of Sonic Responses, a collaboration between the UBC Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery and the School of Music. Performed on the southeast exterior staircase of the Friedman Building at the University of British Columbia located on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territory of the Musqueam people.

[more] -

Event

Sonic Responses: Michael Ducharme

As the final instalment of the Sonic Responses series, we are pleased to present Continuity, a site-specific electro-acoustic composition by Michael Ducharme.

[more]