06 Dec 2021

Outdoor Art: Winter 2021

-

Richard Campbell

Richard Campbell is a Musqueam carver who has been honing his craft for over 40 years. He comes from a family of carvers, including his grandfather, three uncles and many cousins, all of whom have influenced his approach to working in three dimensions. Campbell’s work has evolved from traditional forms to that of a modern, interpretative style.

In addition to working in bas-relief, he has created sculptures of various scales and for different purposes. He was the main carver for the 20’ tall house post in front of the Musqueam Band Office in Vancouver and contributed to the building of the Coast Salish-style longhouse that is part of the collection of the Canadian Museum of History in Hull, Quebec.

Alongside his artmaking practice, Campbell has worked as an archaeologist field assistant with the Musqueam Indian Band for some 23 years. Both occupations reflect his dedication to ensuring his culture lives on for future generations.

Read More

-

James Hart (7idansuu)

Born in 1952 into the Eagle Clan at Old Massett, Haida Gwaii, Haida master carver and hereditary chief 7idansuu James Hart has been carving since 1979. In addition to his monumental sculptures and totem poles, which can be seen at the Museum of Anthropology on campus, he is a skilled jeweler and printer and is considered a pioneer among Haida artists in the use of bronze casting. Hart is the recipient of the Order of British Columbia (2003), an Honorary Doctorate of Letters from the Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design (2004), the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal (2013), and the Audain Prize for Visual Art (2021).

Read More

-

Elza Mayhew

Elza Mayhew (1916–2004) was born in Victoria, BC. She received a BA from UBC (1936) and MFA (1963) from the University of Oregon. Mayhew was known for her abstract sculptures that were typically carved in polystyrene and then cast in aluminum or sometimes bronze. She worked primarily from sketches, rarely from models, and described her work as highly structured and architectural while always relating to the human form. Mayhew produced commissioned works for international events such as Expo 67, Expo 86 and an international trade fair in Tokyo, as well as for public institutions such as the Bank of Canada, the University of Victoria, the Canadian National Capital Commission and the Royal British Columbia Museum. Her work is included in the collections of the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, the National Gallery of Canada, Simon Fraser University and the University of Victoria. Her sculpture Column of the Sea is located at the Confederation Centre of the Arts in Charlottetown. Mayhew was a member of the Royal Canadian Academy, and was an active member of the Limners Society.

Read More

-

Robert Murray

Robert Murray, sculptor, painter, printmaker and art teacher, was born in Vancouver in 1936 and grew up in Saskatoon. He began studying art in Saskatoon, taking courses at the Bedford Road Collegiate High School under Ernest Lindner (1897-1988) and at the Saskatoon Teachers’ College under Wynona Mulcaster (b. 1915). In 1960, after attending the Regina College School of Art (1956-1958) and the Emma Lake Artists’ Workshop led by Barnett Newman in 1959, Murray moved to New York City, where he studied at the Art Students’ League under Will Barnet (1911-2012). As an artist, Murray had started out as a painter and a printmaker but shifted his focus to sculpture beginning in 1959, when he accepted a commission to design a sculptural fountain for Saskatoon City Hall. The commission was Murray’s first attempt at designing large-scale sculptural works in metal fabricating plants. He continued in this vein in subsequent years, designing numerous monumental constructions in steel and aluminum, including the red painted steel sculpture entitled Ferus, which he produced at the Treitel-Gratz factory in New York in 1963. The work was installed on Lookout Island in Georgian Bay, ON and was shown at the Washington Square Gallery, New York in 1964 and at the Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, the following year. It was purchased in 1999 by the National Gallery of Canada, which held a Robert Murray retrospective entitled The Factory as Studio during that year. Along with the National Gallery of Canada, Murray’s work can be found in the collections of the Belkin, the Art Gallery of Ontario (Toronto), the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the New Brunswick Museum (Saint John) and the Whitney Museum of American Art (New York).

Read More

-

Holly Schmidt

Holly Schmidt (Canadian, b. 1976) is an artist, curator and educator engaging in embodied research, collaboration and informal pedagogy. She creates site-specific public projects that lead to experiments with materials in her studio. As the core of her work, Schmidt explores the multiplicity of human relations with the natural world. During her residency with the Belkin’s Outdoor Art Program, Schmidt has utilized spaces between campus buildings through a process of collective knowledge production. These artistic and ecological interventions foster relationships with plants in a manner that is both distinct from the formal, university landscape design as well as from standard notions of gallery space. Schmidt has been involved in exhibitions, projects and residencies at the Belkin Outdoor Art Program; the Burrard Arts Foundation, Vancouver; AKA Gallery, Saskatoon; Charles H. Scott Gallery, Vancouver; the Santa Fe Art Institute; Burnaby Art Gallery; and Other Sights for Artists’ Projects, Vancouver.

Read More

At the Belkin, we often receive questions about the University’s Outdoor Art Collection and what is involved with commissioning, acquiring or accepting donations. Responding to this growing interest, we issue annual outdoor art newsletters to share updates and backstory information about what is involved with curating, stewarding and activating the collection. These newsletters also offer a forum for the Belkin’s curatorial team to share their research and insights about art in public space.

In this edition, we are pleased to feature an essay by Curatorial Assistant and PhD student Julia Trojanowski who considers the work of Elza Mayhew in relation to the notion of the threshold, as well as research by Curatorial Intern Alison Powell.

There are currently 24 artworks in the Outdoor Art Collection, the first of which was installed in 1925 and the most recent in 2021. Tracing the acquisitions decade by decade reveals a narrative of changing societal values and understandings of the role of public art within the unique setting of UBC. Operating as it does within the inherently political space of the public realm, public art poses uniquely accessible opportunities for engagement in which artists and audiences can publicly exchange ideas. Within this edition of the Outdoor Art newsletter, an update about Vancouver-based artist Holly Schmidt’s Fireweed Fields explores how a gesture or action in the outdoor spaces of a university can act as a catalyst for meaningful exchanges between those who live, study and work on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territory of the Musqueam people.

Donations

The most recent donation to the Outdoor Art Collection was Stela I and Stela II (1963) by Elza Mayhew. This pair of abstract, cast aluminum sculptures was the gift of the Mayhew family and was installed on campus through support from the President’s Office and the President’s Advisory Committee on Campus Enhancement. The pair stands in the green space between the Faculty of Dentistry and the UBC Hospital Koerner Pavilion.

With this donation, the university adds to its significant holdings of outdoor art while increasing the representation of women artists in the Outdoor Art Collection, as per the Belkin’s new acquisition strategy. For the next five years or more, the Belkin commits 100% of its acquisition budget to purchasing exclusively works by women artists, including self-identifying LGBTQ2S artists and with a priority given to BIPOC artists. The strength of the Belkin’s overall collection and archives resides in a focus on West Coast artistic practice from the 1950s to the 1970s, and Stela I and Stela II are excellent examples of modernist work produced during that time. Mayhew was an active member of the Limners Society, a Victoria-based group of artists named for the medieval journeymen who would travel from place to place, painting and illustrating to earn their livelihood. The artistic practices of those involved in the Society varied considerably in medium and style, but all were united in their intent to explore the human condition and invigorate Victoria’s contemporary art scene.

The process of finding their ultimate siting to the west of the Faculty of Dentistry (J.B. Macdonald Building) was a measured and reflective one. Director Emeritus Scott Watson initially took notes from the Belkin’s holdings of the British art historian and critic Kenneth Coutts-Smith’s fonds, who wrote about the Stelae in relation to a natural setting.

Modernist architecture of the same era, as well as a rich green space, emerged as potential conversation partners to the Stelae, and both were found outside of the Faculty of Dentistry by Curator of Outdoor Art Barbara Cole and UBC Landscape Architect Dean Gregory. Having gone on a number of walks to scope out potential sites, their attention kept returning to that space in particular. The surrounding architectural elements, the gently mounded landscape and stand of mature pine trees, as well as the materiality of Robert Weghsteen’s organically textured ceramic mural on the Dentistry building itself, offer a layered experience of the Stelae’s relationship to time and place.

Bringing in the perspectives of various participants in this medical precinct of the campus was an important part of selecting this site. The grassy knoll on which the Stelae now stand is one for relaxation for students and patients alike in between classes, labs and medical appointments. An enthusiastic response pushed the siting process forward to the Outdoor Art Subcommittee for feedback, and then to the final step of obtaining a Development Permit. The Belkin’s Owen Sopotiuk and David Steele created mock-ups of the works, which were tested together and apart in various locations on the grass. Having tested the sight lines from various viewpoints, Cole selected their final location, bearing in mind the ways in which the Stelae would enter the space and its dialogues. The works now stand flush with the ground, emerging out of the grass, able to be approached and experienced intimately from a number of directions.

The gift of Stela I and Stela II was publicly celebrated on Saturday, 18 September 2021.

Underway: Bronze Disc, a collaboration between James Hart, 7idansuu (Edenshaw) and Richard Campbell

The Audain Foundation has generously donated funds to support the production of a bronze disc for the base of Reconciliation Pole: Honouring a Time Before, During and After Canada’s Indian Residential Schools (2015-17) by Hereditary Chief James Hart, 7idansuu (Edenshaw).

The pole was erected in 2017 to symbolize the tragedy brought by the residential school system, to memorialize the students who died, to tell the stories of the time before and to present hopes for a more respectful future.

It was part of Hart’s original vision for the pole to include a bronze disc or “skirt” at its base to acknowledge the physical contact point where the artwork meets Musqueam land. Hart invited Musqueam artist Richard Campbell to develop and carve a design that is currently in the process of being cast in bronze to be fitted in sections around the pole.

Having grown up in a family of carvers, Campbell has been honing his craft for over 40 years. The artist has completed pieces within the Vancouver area and in Quebec while also working as an archeologist for the Musqueam Band for 23 years.

In preparation for the carving, Hart worked with Lekwiltok (part of Kwakwaka’wakw First Nation) artist Max Chickite, to fashion a to-scale disc in high density foam for Campbell to carve his design into.

The Belkin and the Department of Art History, Visual Art and Theory (AHVA) worked together to find a suitable work space to accommodate the high density foam disc’s generous scale while providing a valuable open-studio experience for students. Occupying part of AHVA’s third floor BFA studios at the Audain Art Centre, the collaboration between three esteemed artists from Haida, Musqueam and Lekwiltok unfolded. In addition to taking part in aspects of the carving process, visual arts students were invited to drop by to observe the artists working and to ask questions.

AHVA staff were able to connect Hart, Campbell and Chickite throughout the design process through live remote communication technologies – their collaboration thereby becoming accessible to the students, design team, engineers, fabricators and other project contributors. In the final stages, Chickite re-joined the team to finalize the carved design with Campbell and prepare the carved panels for transport to Burton Bronze Foundry on Salt Spring Island. It is anticipated the bronze disc will be completed and installed on campus in the Spring of 2022.

Commissions

Throughout this past year, a number of commissions of different durations aligned programming between the Belkin and the Outdoor Art program to include temporary artworks and musical performances in public spaces across campus. Sonic Responses furthered the collaborations between the Belkin and the School of Music that continued through Soundings: An Exhibition in Five Parts (fall 2020).

Sonic Responses invited eight musicians (six of whom were students) and one composer from the School of Music to respond to the changed aural conditions of UBC’s outdoor spaces during the COVID-19 pandemic lock down. The performers’ music confronted and entered into a dialogue with the eerie quiet that resided on campus through the Spring and Summer months. Through the Belkin’s online Everything This Changes series, videos were rolled out over a number of weeks with descriptions of the place chosen for the performance, the piece selected specifically for that place and the person who performed it.

In the fall, situated within and responding to the constantly evolving health situation, Soundings saw some of the activity of the gallery extending into outdoor spaces. Presented as a touring exhibition that would grow as it traveled to different locations, curators Candice Hopkins and Dylan Robinson proposed the musical score as a critical, political act. Among the works created for outdoor spaces was Musqueam artist Diamond Point’s wəɬ m̓i ct q̓pəθəttə ɬniməɬ, a set of banners that formed two continuous lines down the 1.2 kilometre length of UBC’s Main Mall. The banner images echoed the contours of the lands and waters to the north with depictions of raised panels referencing annual Coast Salish canoe journeys. Related carved and painted paddles installed in the gallery now travel with the exhibition to different lands and territories and also join the works acquired through the gallery’s 2021 acquisitions. For the exhibition launch, Coastal Wolf Pack (Tsatsu Stalqayu) responded to Point’s banners as a musical score by performing a traditional paddle song for the length of the mall.

Other outdoor activations included the performance of Raven Chacon’s American Ledger by the Symphonic Wind Ensemble and a series of School of Music students’ responses to the beaded work of Olivia Whetung performed on the Ladner Clock carillon. One year later, a composition created by Athena Loredo as part of Soundings was re-staged to celebrate students’ return to campus.

Update: Outdoor Art Residency

Vancouver-based artist and educator, Holly Schmidt, will soon begin year four of Vegetal Encounters, her multi-year, slow residency within the Belkin’s Outdoor Art program. A significant component of her residency, Fireweed Fields offers a space for gathering, learning and engaging in actions that address the global climate emergency.

In the spring of 2021 and in collaboration with the Sustainability Initiative and the Botanical Garden’s Horticulture Training Program, Schmidt began the slow process of transforming the Belkin’s lawns into a meadow, thereby encouraging increased biodiversity through a model of ecological succession planting. The project’s title celebrates fireweed as a metaphor for the resurgence of life after a crisis. Fireweed has exceptionally hearty seeds and its sprouts are often the first sign of ecological recovery after a major disturbance. Schmidt suggests there is much to learn from fireweed’s propensity for adaptation, especially in light of this state of climate emergency. As the fireweed plant matures, it creates a nurturing environment for what is to come. As seasons pass, fireweed starts to recede and other meadow plants begin to dominate, attracting insects and animal life. This ecosystem with the right conditions, evolves to a more herbaceous environment, eventually transitioning to a space that includes shrubs and trees. Similarly, the Belkin’s meadow will respond and change over time.

Inspired by the rhizomatic root structure of fireweed, a reclaimed cedar boardwalk designed by Charlotte Falk in collaboration with Schmidt invites visitors to enter into the meadow, a space dedicated to supporting biodiversity research, activities such as workshops and events and meditative contemplation. Wrapping around the building’s front entrance, it also accommodates outdoor seating in proximity to the gallery’s recently installed outdoor digital screen. Documentation of Fireweed Fields’ transformation from manicured lawn to meadow is part of the screen’s programming in addition to scheduled film events that present the pressing need for climate action from other artists’ perspectives.

The Fireweed Fields project also features a second iteration of Forecast, a series of seasonal weather forecasts installed on the clerestory windows of the Belkin and the lobby windows of the CIRS building. These poetic texts are printed on vinyl with a mirror finish and reflect upon the localized effects of weather on humans, plants and animals. Together, the meadow, boardwalk, texts and screen create an immersive experience, engaging visitors in a contemplative relationship with the meadow’s plant and animal inhabitants.

Fireweed Fields also provides an important avenue for the connection between scientific theory and practice on campus. Under the direction of Linda Jennings, Collections Curator for the Beaty Biodiversity Museum Herbarium in the Faculty of Botany and Zoology, specimens are being observed and collected seasonally to document changes in biodiversity over time. This collection will be an important source of data for future research.

Throughout the summer and fall of 2021, a robust and varied program of activities related to Fireweed Fields included a two-day Summer Intensive with invited artists and researchers; drawing workshops with Chrystal Sparrow and participants in the MOA Native Youth program as well as scheduled open-to-the-public events; drawing workshops with AHVA students, MOA Indigenous Internship Program participants and Emerge participants; sensorial walks, “looking labs” and other workshops with SALA students, biology students and environmental science students; with occupational therapy and medical practitioners; guest artist in AHVA and SALA classes; film screenings with the UBC Film Society; and a poetry reading with Dallas Hunt in collaboration with UBC Reads, amongst others.

Refurbishment

In addition to researching, commissioning and supporting artists who are developing projects specific to UBC, the role of the Curator of Outdoor Art is to steward and maintain the existing collection. In the Outdoor Art: Fall 2018 newsletter, we featured Robert Murray’s Cumbria (1966-67/1995), a modernist sculpture that was undergoing restoration.

With refurbishment now complete, Cumbria has been centrally located at the very active intersection of West Mall and University Boulevard. The sculpture is strategically positioned to take advantage of distant views along the slope of the boulevard, its occupation of space distinctly different from the surrounding buildings and landscapes. Viewers can circle Cumbria, a walk that from multiple perspectives, reveals relationships between object and place, colour and form. Striking birds’ eye views can be seen from upper level studios at the Audain Art Centre, Cumbria’s presence a reminder to visual art students of the impact of abstraction in the development of modernist sculpture. Murray spent his formative years as a painter and likens his sculpture to colour field painting; “we were throwing all of the extraneous stuff out the window and trying to get down to the basic moves of the piece.”

Cumbria’s steel planes of bright yellow rise from the concrete platform and extend into the sky as if they are about to take flight. Having been located in downtown Toronto, New York City’s Battery Park, the Vancouver International Airport, and finally UBC’s campus, Cumbria has been presented in a range of contexts, physical sites and situations over the past five decades. Recognizing that time can change a site or a social sphere, Murray welcomes these shifts: “I spend a lot of my time these days trying to find a better location for work. A couple of my friends who used to make what they call ‘site-specific’ sculpture, I used to caution them, [saying] ‘don’t make it too site specific because the site’s going to change,’ and I think, with almost no exceptions, every time I’ve moved a work or helped move a work, it’s gotten better because of what we’ve learned about the piece.”

The launch of the newly-restored Cumbria was held on 18 September 2021. The artist, his partner and various faculty, staff and members of the public were in attendance to celebrate the artwork’s revitalization.

“The Shape of Her Life”: Elza Mayhew’s Engagement with Liminality

By Julia Trojanowski

“I have never made anything not closely connected with the human being and his environment. Man and his longings, desires, his dwellings, the thresholds he passes over and his places of worship concern me; people, buildings, entrances through which people go in, come out; and the apprehension, the pleasure or the peace that accompanies these acts. Passages may suggest revelations of the unknown, and black holes refer possibly to far recesses of the mind.”[1]

Mayhew’s enigmatic sculptures Stela I and Stela II (fig. 1) are made up of nooks and crannies that seem to beckon the viewer to take a look inside. Made of aluminum and cast using a polystyrene mould, they appear as aggregate columns. Blocks and alcoves build on one another, jutting out in places and nestling in as puzzle pieces elsewhere. Interspersed throughout are rectangular apertures resembling windows and doors through which light can travel. The sculptures are approximately the height and width of a human being, and are incised with markings that do not have any specific referent. Thought by the artist to be recognizable if not always legible, they seem to invite the viewer to try their hand at deciphering them. Mayhew’s practice alludes in many ways to ancient architecture, with gates, temples, and passageways often being explicitly identified through their titles.[2] The Stelae, as their titles indicate, refer to monumental carved or incised slabs, and they are no exception to her inclination toward architectural arrangements of space and form. Kenneth Coutts-Smith writes regarding Mayhew’s ambiguous use of scale that “a small niche is emotionally big enough for a tomb, a small opening becomes a towering processional arc de triomphe.”[3] The clusters could just as easily be read as small chambers, stitched together with narrow ducts resembling halls and passageways. Far from being intimidating, their scale renders them anthropomorphic – even inviting.

Stela I and Stela II stand as a pair on a shady hill on the west side of UBC campus. They call to mind a number of ancient markers – stelae, cairns, herms, tombstones – without invoking a particular model. Their titles allude to the stone monuments with which Mayhew would have been familiar as a result of her academic interests and her travels. She majored in French and Latin at UBC, and wrote her BA Honours thesis on the subject of Roman tombstones, which were often ornately carved and inscribed.[4] Aside from their funerary use, stelae could mark boundaries between regions and towns, or function as commemorative monuments. As is the case of Mayhew’s stelae, many ancient examples incorporated architectural elements into their designs. Classical Greek and Roman designs featured pediments and pilasters that would have been familiar from temples, and Old Kingdom stelae that used lintels and architraves to resemble ‘false doors’ for the soul were common in Egypt.[5]

Mayhew’s concern with the concept of the threshold, and the passages that represent the journey between the interior and the exterior, the known and the unknown, evoke a theoretical engagement with liminality. A concept first popularized in anthropological discourse, it has more recently been employed within a much broader range of disciplines. Transitoriness, spatiality, and the negotiation of disparate positions all play a part in defining liminality, though its roots as a term are more specific.[6] First introduced in 1909 by Arnold van Gennep in his book Les Rites de Passage (published in English in 1960), the word “liminal” was used to describe a middle stage in a ritual process, occurring between a “rite of separation,” and a “rite of incorporation.” Rites of passage are moments of social change, exemplified in occasions such as coming of age.[7] The concept was resurrected and popularized by Victor Turner in his essay “Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Period in Rites of Passage” in his Forest of Symbols (1967). Turner reformulated the concept and contributed to current interdisciplinary understandings of liminality as a transformative in-between state within a process.[8] Liminality can be characterized as a period of coalescence or negotiation between what has happened and what will come to be.

A thinker who was engaging concomitantly with questions of the embodied experience of space was Gaston Bachelard, who published his La Poétique de l’Espace in 1958. In this volume, published in English in 1964, he lyrically probes the ways in which we experience and remember intimate spaces. The experience of liminality is inherently experiential, in that it involves passing through something.[9] Taking a nod from the surrealists,[10] he positions his phenomenological method alongside a psychoanalytic one.[11] Mayhew’s understanding of the experience of architecture, her speculation on “man and his longings, desires, and dwellings,”[12] is, too, phenomenological; she is concerned with the ways in which people move through, relate to, and perceive their spaces. Though she expressed that she was uninterested in being psychoanalyzed,[13] her fascination with the “recesses of the mind,” of those secret nooks in which the truth might reside, can only be characterized as a tentative interest, situating her directly in relation to the model utilized by Bachelard in developing his notion of the poetic.[14]

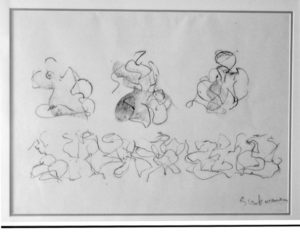

These conversations were not unfamiliar in Canada. Françoise Sullivan was part of Les Automatistes, a group of dissident modernists in Quebec, and was also engaging with anthropology in her surrealist-informed investigations into the unconscious and the mythical. She trained as a dancer with Franziska Boas, daughter of anthropologist Franz Boas, in New York between 1945 and 1947, and strove to integrate what she had learned about developments in the field into her performance practice.[15] Though there is no evidence, as far as I am aware, that Mayhew was following these innovations in modern dance, she nevertheless displayed a parallel interest in the synthesis of dance, sculpture, and myth. She spent many hours alongside some of her colleagues in the Limners Society (a group of artists based in Victoria who were dedicated to invigorating the local art scene) sketching dancers at the Wynne Shaw Dance Studio on Broughton St. (fig. 2). In Mayhew’s drawings these dancers often morphed to take the shape of caryatids, or columns sculpted to take the form of women, which can be found supporting the entablatures of classical Greek temples such as the Erechtheion.[16] The positioning of these sculptures at entryways recalls Mayhew’s consideration of thresholds as transitory spaces.

Janus, the Roman deity associated with thresholds, famously has two faces: one with which to look forward, and one with which to look back. Three of Mayhew’s sculptures – Guardian II, Princess, and Kin – engage formally with this notion, in their ability to “face either of two ways.”[17] This position at the threshold is one that permeates Mayhew’s practice as a whole. Marjorie Garber characterizes modernist engagement with myth as a “quest for universals,” and indeed, looking toward the past – in many instances, an imagined past – for ways through which to negotiate the uncertainty of the present was a typically modernist strategy, employed throughout the 20th century by writers, artists, and scholars.[18] Described evocatively by her daughter, Anne Mayhew, as the “shape of her life,”[19] the Janus figure embodies Mayhew’s conceptual engagement with questions of transition.

Ecofeminism and Public Art

By Alison Powell

Within my graduate studies, I have been investigating convergences between art and environmentalism. Integral to my research is an exploration of environmental philosophies that both shape and emerge from artistic representations of nature. Upon gaining familiarity with the Belkin’s Outdoor Art program, I encountered women artists that centre the human-earth relationship within their works. I have therefore taken this opportunity to highlight the voices of a few of these artists through an ecofeminist lens.

It is first helpful to uncover the meaning of ecofeminism within the context of women’s environmental activism in British Columbia. The Encyclopedia Britannica describes ecofeminism as a theory that “emphasizes the ways both nature and women are treated by patriarchal (or male-centered) society.”[20] However, this connection between women and nature has spurred debates around essentialism, particularly within feminist theory during the 1990s.[21] As Niamh Moore-Cherry explains within her book, The Changing Nature of Eco/Feminism: Telling Stories from Clayoquot Sound, feminist scholars during this decade were combatting historic characterizations that positioned women as being especially attuned to nature contrary to their male counterparts because of their perceived roles as passive nurturers.[22] As a result, ecofeminism was accused of reinforcing biological determinism.[23] Moore-Cherry problematizes this notion and explores the ways in which her experience working within a female-led environmental movement reshaped her understanding of the term.[24]

In 1993, Moore-Cherry travelled to Vancouver Island from the UK to research ecofeminist practices at the Friends of Clayoquot Sound (FOCS) peace camp.[25] The camp was created to protest clearcutting in British Columbia’s temperate rainforest by MacMillan Bloedel. FOCS had made a commitment to practice feminist principles of non-violent civil disobedience, inclusivity and a recognition of the patriarchal dimensions of colonialism and deforestation.[26] In response to the protests at Clayoquot Sound, the provincial government made significant changes to its policies surrounding forestry, indicating the success the movement achieved. It is important to note that the protests were occurring within a quickly shifting landscape of feminist theory. The categorization of feminism as being exclusively tied to women was being brought into question – the term was beginning to be defined less under the umbrella of identity politics and more as a call to engage with “process and practice,” as described by the author.[27] With this understanding, ecofeminism is not simply a framework for connecting women to nature, it is an interdisciplinary method for applying feminist practices to civic action.

This marks a sharp turning point in environmental history where theorists sought to discover not only what destroys nature but also who perpetuates its destruction and through which systems of privilege and oppression. American scholar, activist and documentary filmmaker Greta Gaard explains: “Ecofeminism is based not only on the recognition of connections between the exploitation of nature and the oppression of women across patriarchal societies. It is also based on the recognition that these two forms of domination are bound up with class exploitation, racism, colonialism, and neocolonialism.”[28] This is illustrated within an advertisement circulated by MacMillan Bloedel that exclaimed “we came, we sawed, we conquered.”[29] While the following artists have not explicitly described themselves as ecofeminists, the works of Myfanwy MacLeod, Marianne Nicholson and Holly Schmidt offer points of entry for exploring ecofeminist themes within the context of public art.

Embedded within Myfanwy MacLeod’s Wood for the People (2002) is an ironic relationship between romanticized pastoral landscapes and the industrial exploitation of nature within the early colonial era. The artist describes this work as a subversion of the “folly,” a purely ornamental structure of 18th century France that was built to decorate gardens of the wealthy.[30] Instead, the viewer is met with a pile of 214 identical cast concrete logs stacked outdoors. In this sense, the artist seeks to reference the rustic wooden outposts of North America’s colonial past that heavily influences the relationship between settler society and the natural environment today.[31] The use of concrete makes the wood appear fossilized, perhaps serving as a tomb for an old growth tree. Imagery of the chopped wood, of course, conjures notions of logging practices which razed BC’s West Coast. The work’s title, Wood for the People, creates tension between nature and ownership, bringing into question for whom nature is reserved within the context of imperialism. Moore-Cherry describes how the women’s work of living in the Clayoquot camp involved “trying to resist being a settler, trying not to be implicated in the destruction of nature, but taking seriously the question of how to make a home in nature.”[32] While every person who now resides in Canada has inherited legacies of colonialism, one answer to Moore-Cherry’s question is to resist sanitized and glorified conceptions of the landscape.

Also focusing on contentions between ownership and the natural environment, Marianne Nicolson’s The Sun is Setting on the British Empire (2016) elucidates the ways in which Indigenous people were denied rights to the Canadian landscape. This piece, which is no longer on view, was first mounted on the exterior of the gallery in 2017 as part of the exhibition To refuse/To wait/To sleep and remained until 2020. Here, the artist subverts the iconography of BC’s provincial flag to remind us of its original meaning. While the earliest iteration of the flag once represented partnerships between the crown and Indigenous nations, the flag we are most familiar with places the Union Jack as the primary element of design in celebration of its status as a colony of England. By inverting the design and inserting Northwest Coast Indigenous text and symbols into the image, Nicolson asserts the need to challenge colonial authority, including ongoing threats to unceded territories due to industrial development and resource extraction across the country. Environmental sociologist Dorceta E. Taylor explains that environmental theories largely come from “white middle-class male” perspectives.[33] While settler society formulated its approach to environmentalism, its “inability to recognize the limits of that agenda” has caused marginalized groups to form alternative agendas to address cultural and social inequalities embedded within the environmental movement itself.[34] Nicholson’s work reveals the ways in which Indigenous Peoples have been disproportionately affected by environmental degradation and Indigenous leaders are often found at the frontlines of the battle for environmental protection.

Holly Schmidt’s project at the Belkin, Fireweed Fields (2021-ongoing), further problematizes colonial legacies within her works. By supplanting manicured grass lawns with native species, such as fireweed, yarrow and lupins, the piece has a profound historical and cultural significance for Schmidt. Sensitive to her position as a non-Indigenous settler working within the unceded territory of Musqueam, she envisions manicured grass as a mark of lingering colonial ideals in need of being dismantled. “The history of lawns begins with aristocratic British estates in the 18th century, inspiring American plantations and later proliferating in post-war North American suburbs. The lawn is a symbol of colonization as it suppresses ecological and cultural diversity while requiring significant resources such as water, fertilizer and labour,” notes the artist.[35] Schmidt sees western conceptions of the natural environment as an “extraction” of knowledge: “I think that is quite a limited relationship to have, particularly to the natural world around us.”[36]

Ecofeminist theory has influenced Schmidt’s artistic practice and has inspired her interest in relating to the environment through the senses.[37] Within Fireweed Fields the artist relates the interconnection of the plant’s rhizomes both literally and metaphorically to creative and embodied human interactions with nature. By facilitating sensorial exercises such as careful listening and meditative contemplation, Schmidt prompts participants to understand that the human-earth relationship is one between beings.[38] In May 2021 The Tyee featured an article by Dorothy Woodend on UBC professor of Forest and Conservation Sciences Suzanne Simard’s book Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest, which looks at communication systems between trees through interconnected systems of fungi.[39] For Simard, early Western colonial conceptions of nature positioned the environment as sublime, foreboding, dangerous and in need of taming; however, scientific evidence suggests that, in fact, forests are predicated on “co-operation, mutual support, reciprocity and a level of almost… maternal caring.”[40] This challenges the negative connotation that essentialism has placed on the connection between women and nature. While Simard has been critiqued for her views, she asserts that this has largely been at the root of women’s exclusion from discourse on resource management.[41] By seeing the human-earth relationship as “one that has the power to change me as much as the plant,” Schmidt envisions this as a key pathway to contend with the climate crisis.[42] Schmidt’s work offers a tangible glimpse into the pathway forward. It suggests that to evolve from an empirical understanding of nature born of Enlightenment thinking we must make room for an experiential field of environmentalism.

Similar to the idea that Western patriarchal society has negatively affected women and people of colour, a brief exploration of ecofeminist theory offers insights into the ways in which this dynamic has manifested within Western conceptions of the North American landscape. MacLeod, Nicolson, and Schmidt serve as just a few examples of the ways in which women are leading an increasing environmental focus within public art, and while doing so, are centering the role of colonial history within their critiques. While there is a growing body of ecofeminist literature that assists in addressing this trend, there remains much more room for further considerations of the relationship between ecofeminism and public art. Studies have shown that individuals who support feminist goals, regardless of their gender, are more likely to be concerned about the environment.[43] Returning to my definition of ecofeminism as an avenue for civic action, artworks are increasingly taking on the role of protest in the public sphere and their potential to promote awareness about complex cultural and environmental issues continues to inspire.

IMAGES (FROM TOP): Fireweed Fields Drawing Workshop. Photo: Rachel Topham Photography; elza Mayhew, Stela I and Stela II (1963). Photo: Rachel Topham Photography;

Elza Mayhew, Stela II (1963). Photo: Rachel Topham Photography; 7idansuu, James Hart, Reconciliation Pole (2017). Photo: Paul Joseph; Richard Campbell, Max Chickite, and Students with Bronze Disk (2021). Photo: Jeremy Jaud; Coastal Wolf Pack interpreting Diamond Point’s wəɬ m̓i ct q̓pəθət tə ɬniməɬ (2020). Photo: Rachel Topham Photography;

Holly Schmidt, Fireweed Fields (2021). Photo: Rachel Topham Photography; Holly Schmidt, Forecast (2021). Photo: Rachel Topham Photography; artists Holly SChmidt and Chrystal Sparrow in front of Fireweed Fields (2021). Photo: Rachel Topham Photography; Robert Murray, Cumbria (1966-67/95). Photo: Rachel Topham Photography.

Artist Robert Murray in front of Cumbria (1966-67/96). Photo: Rachel Topham Photography; ELZA MAYHEW, STELA I AND STELA II (1963). PHOTO: RACHEL TOPHAM PHOTOGRAPHY; ELZA MAYHEW, SCRUBWOMEN, DATE UNKNOWN. COURTESY OF ANNE MAYHEW; Marianne Nicolson, the sun is setting on the british empire (2016); Holly Schmidt, Fireweed Fields (2021). Artist’s rendering.

-

Richard Campbell

Richard Campbell is a Musqueam carver who has been honing his craft for over 40 years. He comes from a family of carvers, including his grandfather, three uncles and many cousins, all of whom have influenced his approach to working in three dimensions. Campbell’s work has evolved from traditional forms to that of a modern, interpretative style.

In addition to working in bas-relief, he has created sculptures of various scales and for different purposes. He was the main carver for the 20’ tall house post in front of the Musqueam Band Office in Vancouver and contributed to the building of the Coast Salish-style longhouse that is part of the collection of the Canadian Museum of History in Hull, Quebec.

Alongside his artmaking practice, Campbell has worked as an archaeologist field assistant with the Musqueam Indian Band for some 23 years. Both occupations reflect his dedication to ensuring his culture lives on for future generations.

Read More

-

James Hart (7idansuu)

Born in 1952 into the Eagle Clan at Old Massett, Haida Gwaii, Haida master carver and hereditary chief 7idansuu James Hart has been carving since 1979. In addition to his monumental sculptures and totem poles, which can be seen at the Museum of Anthropology on campus, he is a skilled jeweler and printer and is considered a pioneer among Haida artists in the use of bronze casting. Hart is the recipient of the Order of British Columbia (2003), an Honorary Doctorate of Letters from the Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design (2004), the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal (2013), and the Audain Prize for Visual Art (2021).

Read More

-

Elza Mayhew

Elza Mayhew (1916–2004) was born in Victoria, BC. She received a BA from UBC (1936) and MFA (1963) from the University of Oregon. Mayhew was known for her abstract sculptures that were typically carved in polystyrene and then cast in aluminum or sometimes bronze. She worked primarily from sketches, rarely from models, and described her work as highly structured and architectural while always relating to the human form. Mayhew produced commissioned works for international events such as Expo 67, Expo 86 and an international trade fair in Tokyo, as well as for public institutions such as the Bank of Canada, the University of Victoria, the Canadian National Capital Commission and the Royal British Columbia Museum. Her work is included in the collections of the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, the National Gallery of Canada, Simon Fraser University and the University of Victoria. Her sculpture Column of the Sea is located at the Confederation Centre of the Arts in Charlottetown. Mayhew was a member of the Royal Canadian Academy, and was an active member of the Limners Society.

Read More

-

Robert Murray

Robert Murray, sculptor, painter, printmaker and art teacher, was born in Vancouver in 1936 and grew up in Saskatoon. He began studying art in Saskatoon, taking courses at the Bedford Road Collegiate High School under Ernest Lindner (1897-1988) and at the Saskatoon Teachers’ College under Wynona Mulcaster (b. 1915). In 1960, after attending the Regina College School of Art (1956-1958) and the Emma Lake Artists’ Workshop led by Barnett Newman in 1959, Murray moved to New York City, where he studied at the Art Students’ League under Will Barnet (1911-2012). As an artist, Murray had started out as a painter and a printmaker but shifted his focus to sculpture beginning in 1959, when he accepted a commission to design a sculptural fountain for Saskatoon City Hall. The commission was Murray’s first attempt at designing large-scale sculptural works in metal fabricating plants. He continued in this vein in subsequent years, designing numerous monumental constructions in steel and aluminum, including the red painted steel sculpture entitled Ferus, which he produced at the Treitel-Gratz factory in New York in 1963. The work was installed on Lookout Island in Georgian Bay, ON and was shown at the Washington Square Gallery, New York in 1964 and at the Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, the following year. It was purchased in 1999 by the National Gallery of Canada, which held a Robert Murray retrospective entitled The Factory as Studio during that year. Along with the National Gallery of Canada, Murray’s work can be found in the collections of the Belkin, the Art Gallery of Ontario (Toronto), the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the New Brunswick Museum (Saint John) and the Whitney Museum of American Art (New York).

Read More

-

Holly Schmidt

Holly Schmidt (Canadian, b. 1976) is an artist, curator and educator engaging in embodied research, collaboration and informal pedagogy. She creates site-specific public projects that lead to experiments with materials in her studio. As the core of her work, Schmidt explores the multiplicity of human relations with the natural world. During her residency with the Belkin’s Outdoor Art Program, Schmidt has utilized spaces between campus buildings through a process of collective knowledge production. These artistic and ecological interventions foster relationships with plants in a manner that is both distinct from the formal, university landscape design as well as from standard notions of gallery space. Schmidt has been involved in exhibitions, projects and residencies at the Belkin Outdoor Art Program; the Burrard Arts Foundation, Vancouver; AKA Gallery, Saskatoon; Charles H. Scott Gallery, Vancouver; the Santa Fe Art Institute; Burnaby Art Gallery; and Other Sights for Artists’ Projects, Vancouver.

Read More

End Notes

Elza Mayhew, “Artist’s Statements,” Elza Mayhew, accessed November 22, 2021,

http://www.elzamayhew.com/about.html“Small Sculptures,” Elza Mayhew, accessed November 22, 2021. http://www.elzamayhew.com/small-sculptures.html.

Excerpt from Kenneth Coutts-Smith’s unpublished essay “Rites of Passage: the sculpture of Elza Mayhew,” 1972. Quoted in “Artist’s Statements and miscellaneous notes,” About Elza, accessed November 22, 2021, http://www.elzamayhew.com/about.html.

Scott Watson, “Outdoor Art Launch: Works by Mayhew and Murray,” YouTube video, 38:05, Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, The University of British Columbia, September 18, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xhrD-PzywEE.

Dominique, Collon, Nigel Strudwick, Margaret Lyttleton, Peter Wiedehage, Sheila S. Blair, Elizabeth P. Henson, and Madeline McLeod, “Stele.” Grove Art Online, 2003; Accessed October 25, 2021. https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000081249.

Bjørn Thomassen, Liminality and the Modern: Living through the in-between (Taylor and Francis, 2016), 1-2. doi:10.4324/9781315592435.

Thomassen, Liminality and the Modern, 3.

Don Handelman, “Turner, Victor,” In Encyclopedia of Semiotics (Oxford University Press, 1998). https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195120905.001.0001/acref-9780195120905-e-288.

Thomassen, Liminality and the Modern, 5.

Joan Ockman, “The Poetics of Space by Gaston Bachelard,” Harvard Design Magazine, accessed November 27, 2021, http://www.harvarddesignmagazine.org/issues/6/the-poetics-of-space-by-gaston-bachelard. An anthropological approach was also paramount in the formulation of surrealist perspectives on the relationship between the unconscious and the mythical; see Clifford 1988.

Roch C. Smith, “Bachelard, Gaston,” in Encyclopedia of Aesthetics (Oxford University Press, 1998). https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195113075.001.0001/acref-9780195113075-e-0057.

Mayhew, “Artist’s Statements.”

Phone interview with Anne Mayhew, October 18, 2021. My sincerest thanks to Elza Mayhew’s daughter, Anne Mayhew, for taking the time to share with me her valuable insights into Mayhew’s practice.

Mayhew, “Artist’s Statements.”

Annie Gérin, “Biography,” in Francoise Sullivan Life and Work, (Toronto, ON: Art Canada Institute, 2018). https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/francoise-sullivan/.

Phone interview with Anne Mayhew, October 18, 2021.

“Free-Standing Sculptures,” Elza Mayhew, accessed November 29, 2021. http://www.elzamayhew.com/free-standing-sculptures.html

Marjorie Garber, “Ovid, Now and Then,” Critical Inquiry 40, no. 1 (2013): 142. https://doi.org/10.1086/673229.

Phone interview with Anne Mayhew, October 18, 2021.

Encyclopedia Britannica, “Ecofeminism,” https://www.britannica.com/topic/ecofeminism

Niamh Moore-Cherry, The Changing Nature of Eco/Feminism: Telling Stories from Clayoquot Sound (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2016), 5-6.

Ibid., 7, 8.

Ibid. 9.

Ibid., 8.

Ibid., 28

Ibid., 3.

Ibid., 28-29.

Greta Gaard and Patrick D. Murphy, Ecofeminist Literary Criticism: Theory, Interpretation, Pedagogy (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 3.

Moore-Cherry, 98.

Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, “Myfanwy MacLeod discusses Wood for the People (2002) with Chris Gaudet,” August 26, 2016 interview, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3GOLL_HVtls.

Ibid.

Moore-Cherry, 91.

Dorceta E. Taylor, “American Environmentalism: The Role of Race, Class and Gender in Shaping Activism 1820-1995,” Race, Gender & Class 5, no. 1 (1997): 16.

Taylor, 56.

Holly Schmidt, project proposal for Fireweed Fields, 2021.

Holly Schmidt, interview by author, Vancouver, March 30, 2021.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Dorothy Woodend, “’Mother Trees’ Are Real. They Model Sharing and Generosity,” The Tyee (May 3 2021), https://thetyee.ca/Culture/2021/05/03/Mother-Trees-Model-Sharing-Generosity/?utm_source=weekly&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=030521.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Mark Somma and Sue Tolleson-Rinehart, “Tracking the Elusive Green Women: Sex, Environmentalism, and Feminism in the United States and Europe,” Political Research Quarterly 50, no. 1 (1997): 164.

Related

-

Event

Saturday 18 Sep 2021, 2:15 pm

Outdoor Art Launch: Works by Mayhew and Murray

Please join us on Saturday, 18 September 2021 between 2:15 and 4 pm to celebrate the installation of Elza Mayhew's Stela I and II (1963) and Robert Murray's Cumbria (1966-67/1995). UBC President Santa Ono, Director Emeritus Scott Watson, Professor Emeritus John O’Brian and Curator Keith Wallace will be present to share remarks on the artworks; Cumbria artist Robert Murray will be in attendance.

[more] -

Tour

Saturday 28 September 2019 from 1-2:15 pm

Sunday 29 September 2019 from 1-2:15 pm

Outdoor Art Tour: BC Culture Days 2019

The Belkin is offering a special tour in collaboration with the Museum of Anthropology for BC Culture Days. The event will begin with a guided tour of highlights from the UBC Outdoor Art Collection, led by the Belkin, followed by a tour of outdoor artwork at the Museum of Anthropology led by the Museum. To join the tour, meet the Belkin's Information Desk at 12:50 pm on Saturday, September 28.

[more] -

News

01 Apr 2017

Barbara Cole Appointed as Curator of Outdoor Art

[more]

[more] -

News

02 Dec 2019

Outdoor Art: Winter 2019

[more]

[more] -

News

14 Nov 2018

Outdoor Art: Fall 2018

[more]

[more]