30 Apr 2020

Holly Schmidt: It All Started with a Cashew

-

Holly Schmidt

ArtistHolly Schmidt (Canadian, b. 1976) is an artist, curator and educator engaging in embodied research, collaboration and informal pedagogy. She creates site-specific public projects that lead to experiments with materials in her studio. As the core of her work, Schmidt explores the multiplicity of human relations with the natural world. During her residency with the Belkin’s Outdoor Art Program, Schmidt has utilized spaces between campus buildings through a process of collective knowledge production. These artistic and ecological interventions foster relationships with plants in a manner that is both distinct from the formal, university landscape design as well as from standard notions of gallery space. Schmidt has been involved in exhibitions, projects and residencies at the Belkin Outdoor Art Program; the Burrard Arts Foundation, Vancouver; AKA Gallery, Saskatoon; Charles H. Scott Gallery, Vancouver; the Santa Fe Art Institute; Burnaby Art Gallery; and Other Sights for Artists’ Projects, Vancouver.

Read More

by Ilaria Casini

During these days of physical distancing and deserted campus spaces like the gallery, the lab, the farm, we find ourselves recalling the strength of collaborations over the past year and ways we might reimagine them in the context of an emerging new reality. Last fall 2019, Shelly Rosenblum, Belkin Curator of Academic Programs, Holly Schmidt, Belkin Artist in Residence and Brett Couch, Senior Instructor in the Departments of Botany and Zoology worked together to create novel pedagogical experiences for students in a third year biology course on Mycology. We came together to consider how our research and teaching methodologies might mutually inform one another’s practices, both in terms of obstacles and achievements, and how to use these insights to enhance and enrich students’ experiences.

This is how it all started with a cashew – a simple task to spark creativity and ignite recollection. Holly began her workshop with a simple request inspired by a New York Times article, “A Simple Way to Better Remember Things: Draw a Picture,” asking everyone to sketch a cashew and then put the drawing away. Only a week later would the cashew gain significance.

Did the group recall what Holly had asked them to draw, a task that seemed arbitrary at the time? They did. Their hands had engaged in a tactile activity, as if the mark had imprinted on their brain, proving the mnemonic capacity of drawing to create knowledge. The cashew was not only mentioned, seen or talked about, it was made. With this simple task, Schmidt’s aim was to illustrate the benefit of an embodied experience: of praxis over theory. As part of Vegetal Encounters, a three-year artist residency with the Belkin’s Outdoor Art Program, Schmidt is hoping to engage with a diverse public connecting different communities and departments across UBC. Schmidt’s work aims to fill an ever broadening gap between branches of human knowledge and to bridge art and science in terms of both method and content. The artist’s involvement with the biology department builds on the Belkin Academic Programs’ mandate to reflect on how the arts contribute to the creation of different epistemologies and how the gallery space fits within the university as a site of research and knowledge creation.

Her engagement with BIOL 323 took place over three weeks: in the biological sciences lab, at the UBC Farm and at the Belkin Art Gallery. What does it mean for students today to engage with observational skills in a discipline such as botany, which has seen the gradual disappearance of drawing as a research tool? Schmidt’s interest does not actually lie in teaching technique and assessing the accuracy of the students’ drawings. The attention is directed towards the investigative act of observation itself, how to look for certain pieces of information and how to extrapolate them and represent them through drawing. Even more importantly, how to construct knowledge together with non-human agents, to creatively engage with plants (and fungi) as a significant source of life, connection and learning.

Holly reminded the students that learning with plant life involves slowing down and using all of the senses to engage deeply and with respect. Observation suddenly debunks the superiority of the sense of sight. Walking through the Agroforestry Trail Walk on a glorious September day in Vancouver – humidity and dampness, wetness of the leaves on the hands and legs, slipperiness of the ground, pungency of the soil and vegetation – whack one’s perception as much as the green of the foliage, the browns and umbers, the depth of field of the infinite forest grounds overlapping one another. One does not only see the ruggedness of a tree trunk but feels its texture under the fingertips. How do we transpose that information into drawing? Likewise, what does a sound look like? How might we transcribe sounds in order to revisit it once it is over in relation to the rest of the findings? Not by recording it in order to reproduce it exactly. Again, the aim is not mimesis, the cashew was not photographed in that first class. Instead, how does the sound appear to me specifically? Catapulted forward another week, the students of BIOL 323 were invited to listen to a different “landscape” than the UBC Farm. Inside the Belkin, bodies of water from around the world were crashing together to raise important environmental issues through the exhibition, Spill. Schmidt encouraged the students to listen to the Columbia River inside Genevieve Robertson’s Still Running Water projection. The waves, the dripping, the silence, the scraps of wood being pushed aside, the drone-like buzzing, the emptiness of landscapes resurfacing from reservoirs, all emerged in ink on the students’ notebooks. In the form of dashes, wavy lines, dots, strokes and jagged marks they composed a personal score, not of what Robertson’s piece sounded like, but of what it felt like. Botanical drawing taken to abstraction.

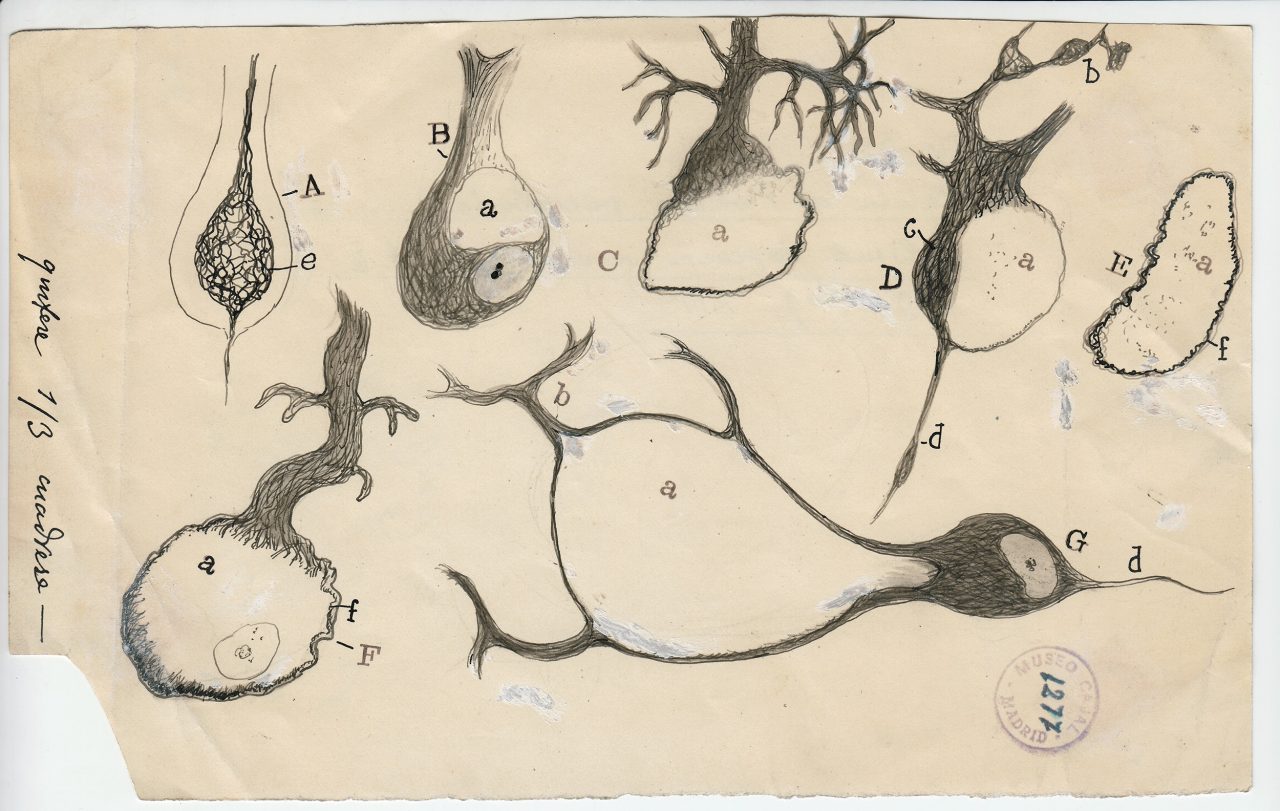

The question is why not? The mimesis of botanical drawing is something the biological sciences have understood as the best way for representing and cataloguing the natural world. Herbaria house collections of drawings representing the holotype of each species, that is, a single type specimen upon which the description and name of a new species is based. A perfect form, the canon onto which comparing every single case in existence. Yet if we know one thing for sure, it is that Nature does not work on a mold production. Anomalies and irregularities seem to represent the norm more accurately than a perfect type zero. Holly Schmidt confronts this philosophical understanding of the discipline of biology. During the drawing exercises with the samples collected on the Agroforestry Trail or those lent by the Beaty Biodiversity Museum, students struggled to move past their comfortable way of drawing, the expectations and the training of the scientific discipline. They were encouraged to focus on the journey of their selected specimen instead of its shape, to use the margins, think of the gesture itself of drawing, animate the specimen with their minds, to look for idiosyncrasy more than mimesis. Working outside mimesis does not mean working against the discipline research or data collection. Embodied investigations — walking, touching, drawing, swimming, smelling – can implement theoretical or lab-oriented research. You might recall the Belkin’s 2017 exhibition The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Rámon y Cajal. In the late 19th century, neuroscientist Rámon y Cajal, discovered that nervous tissue was not a single continuous tangled network, but was in fact made up of individual cells called neurons through the use of hand-drawn illustration to help elaborate what he observed in the microscope. Cajal’s drawings represent a synthesis of a scientific thought, not merely a reproduction. His work is one of the most successful examples of a different engagement with visual material, where an artistic embodied practice can contribute towards scientific research. In fact, his drawings are still used in contemporary medical publications to illustrate important neuroscience principles, and continue to fascinate artists and visual art audiences.

A final discussion made some students linger on after all the drawing exercises, silent walks and immersive encounters, maybe the cashew was even mentioned again? There is a radical potential inherent in such hybrid projects, the possibility of encounter amongst disciplines. The Belkin has an ongoing commitment to interdisciplinary dialogue, such as the Art and Medicine: Rounding at the Belkin program, directed at first-year medical students. This course is aimed at improving observational skills used in diagnosis, and interpersonal communication with colleagues and patients through visual analysis of artworks and discussion around a selection of essays and academic articles in visual theory. Holly Schmidt’s work with the Mycology class did not set out to lecture biology students on the visual arts but to agitate a new way of being and learning, to engage in tactical experiences which will impact the long term reflection on the subject.

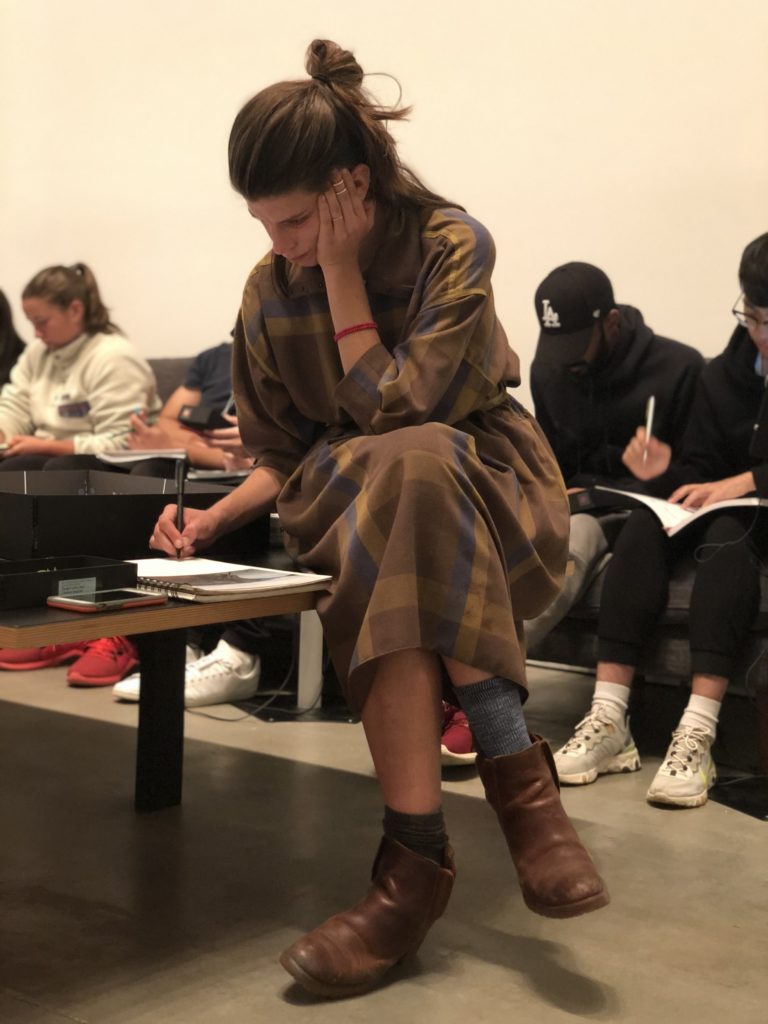

BIOL 323 student drawing in the Belkin Art Gallery, October 2019

Artist Holly Schmidt and BIOL 323 students drawing at UBC Farm, October 2019

Image (above): Artist Holly Schmidt (centre) with BIOL 323 students at the UBC Farm, September 2019

-

Holly Schmidt

ArtistHolly Schmidt (Canadian, b. 1976) is an artist, curator and educator engaging in embodied research, collaboration and informal pedagogy. She creates site-specific public projects that lead to experiments with materials in her studio. As the core of her work, Schmidt explores the multiplicity of human relations with the natural world. During her residency with the Belkin’s Outdoor Art Program, Schmidt has utilized spaces between campus buildings through a process of collective knowledge production. These artistic and ecological interventions foster relationships with plants in a manner that is both distinct from the formal, university landscape design as well as from standard notions of gallery space. Schmidt has been involved in exhibitions, projects and residencies at the Belkin Outdoor Art Program; the Burrard Arts Foundation, Vancouver; AKA Gallery, Saskatoon; Charles H. Scott Gallery, Vancouver; the Santa Fe Art Institute; Burnaby Art Gallery; and Other Sights for Artists’ Projects, Vancouver.

Read More

Related

-

Event

1-6 June 2019

Holly Schmidt’s Forecast at the Audain Centre

[more]

[more] -

News

14 Nov 2018

Outdoor Art: Fall 2018

[more]

[more] -

Exhibition

3 September – 1 December 2019

Spill

Involving installations, live research, performance and radio programming, Spill is curated by Lorna Brown and presents work by Carolina Caycedo, Nelly César, Guadalupe Martinez, Teresa Montoya, Anne Riley, Genevieve Robertson, Susan Schuppli and T’uy’t’tanat Cease Wyss. Spill: Response, curated by Guadalupe Martinez, re-centres the gallery as a site for embodiment, with visiting artist César in collaboration with Riley and Wyss. Throughout the project, Spill: Radio, curated by Tatiana Mellema, will present radio episodes in collaboration with CiTR 101.9 FM.

[more] -

Exhibition

5 September 2017 – 3 December 2017

The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal

The Beautiful Brain is the first North American museum exhibition to present the extraordinary drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852–1934), a Spanish pathologist, histologist and neuroscientist renowned for his discovery of neuron cells and their structure, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1906. Known as the father of modern neuroscience, Cajal was also an exceptional artist and studied as a teenager at the Academy of Arts in Huesca, Spain. He combined scientific and artistic skills to produce arresting drawings with extraordinary scientific and aesthetic qualities. A century after their completion, his drawings are still used in contemporary medical publications to illustrate important neuroscience principles, and continue to fascinate artists and visual art audiences. Eighty of Cajal’s drawings are accompanied by a selection of contemporary neuroscience visualizations by international scientists.

[more] -

Event

2021-24

Holly Schmidt: Fireweed Fields

Fireweed Fields transforms a UBC lawn site into a fireweed meadow, encouraging increased biodiversity through gradual succession as a metaphor for the resurgence of life after a crisis. This installation acknowledges the global climate emergency: by tearing through the fabric of maintained lawns and colonial ideals, it plants the initial seeds for change and catalyzes dialogue, creative experimentation, and new biodiversity research and learning opportunities.

[more] -

Event

Spring 2020

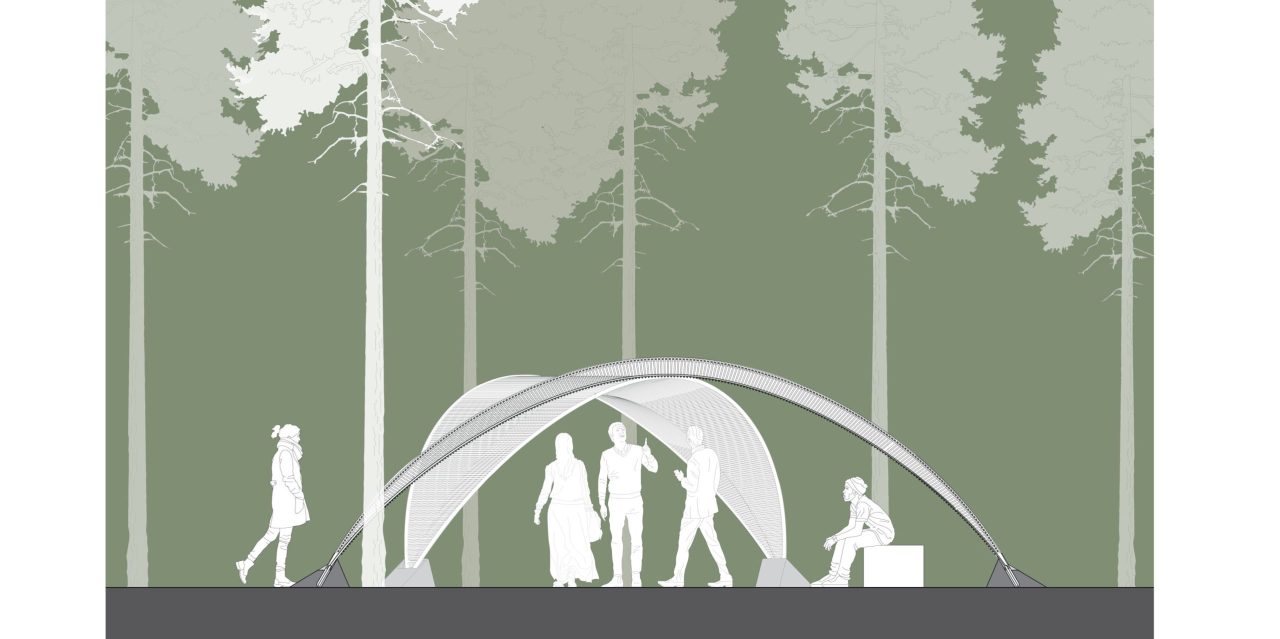

Holly Schmidt: Nomadic Structures

As part of Holly Schmidt's Vegetal Encounters residency, the artist has collaborated with Lecturer Bill Pechet and students from UBC’s Environmental Design (ENDS) program, in the School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture to explore the potential for a mobile structure to support residency programming on campus.

[more] -

Exhibition

January 2019 – April 2024

Holly Schmidt: Vegetal Encounters Residency

Vegetal Encounters is Holly Schmidt’s three-year residency with the Outdoor Art Program at UBC. Through this residency, Schmidt has been creatively engaging with plant life as a significant source of life, connection and learning.

[more] -

News

19 Mar 2020

Holly Schmidt: Accretion

[more]

[more] -

News

30 Apr 2020

Holly Schmidt: It All Started with a Cashew

Students from UBC’s Department of Biology practice botanical drawing – and immersive observation – with artist in residence Holly Schmidt.

[more] -

News

04 May 2020

Holly Schmidt: Sensorial Walk

Download and print the sensorial workshop Holly Schmidt devised for UBC mycology students and enjoy nature a little differently.[more]

Download and print the sensorial workshop Holly Schmidt devised for UBC mycology students and enjoy nature a little differently.[more] -

News

01 May 2020

Twenty-minute Walk with Holly Schmidt

The Belkin’s Lorna Brown talks with artist in residence Holly Schmidt about her practice and its relationship to care, distance and embodiment in this very particular historical moment.

[more]