20 Jan 2023

Works from the Collection: Charmian Johnson

-

Charmian Johnson

Charmian Johnson (Canadian, 1939-2020) was an artist and educator who lived and worked in Vancouver. She studied ceramics under Glenn Lewis, and developed a distinct style within the Leachian tradition having spent a number of years at Bernard Leach’s pottery studio in St. Ives where she catalogued and archived the Leach collection. Beginning in the 1970s, Johnson has been highly regarded across local and international ceramic communities. Throughout her lifetime, she developed a meticulous drawing practice that she kept largely to herself. Rendering botanical elements she encountered in her own garden as well as on her travels to Morocco, Turkey, Hawaii and France, Johnson developed her drawings over time, sometimes for months or even years. Johnson studied drawing, graphics and pottery at the University of British Columbia. She has had solo exhibitions at the Vancouver Art Gallery and UBC Fine Arts Gallery (now the Belkin Gallery). Johnson has been featured in group exhibitions across Canada, including the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; the UBC Museum of Anthropology, Vancouver; the Burnaby Art Gallery; the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria; the Glenbow Museum, Calgary; the Museum of Natural Sciences, Ottawa; Catriona Jeffries Gallery, Vancouver; and in the 2004 exhibition Thrown: Influences and Intentions of West Coast Ceramics at the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, which she co-curated.

Read More

“… epimedium and some divisions of tall blue Siberian iris, one side shoot of Japanese toad lily, and a little pot of…” 1

Like stepping through a greenhouse. Ducking between vines and leaves and flowers as lush and thick as layers of pottery set and scattered throughout the studio. Feeling the light cast through the window, then through the pane of veins of broad leaves and petals. Charmian Johnson kept her house and studio something like this, so I hear – a place full of ways of looking quietly, looking intently, and the vibrancy of growing things.

“… our native spring blooming primula, planted to grow in the half shade for a while until they root in for transplant are all together here at house…”2

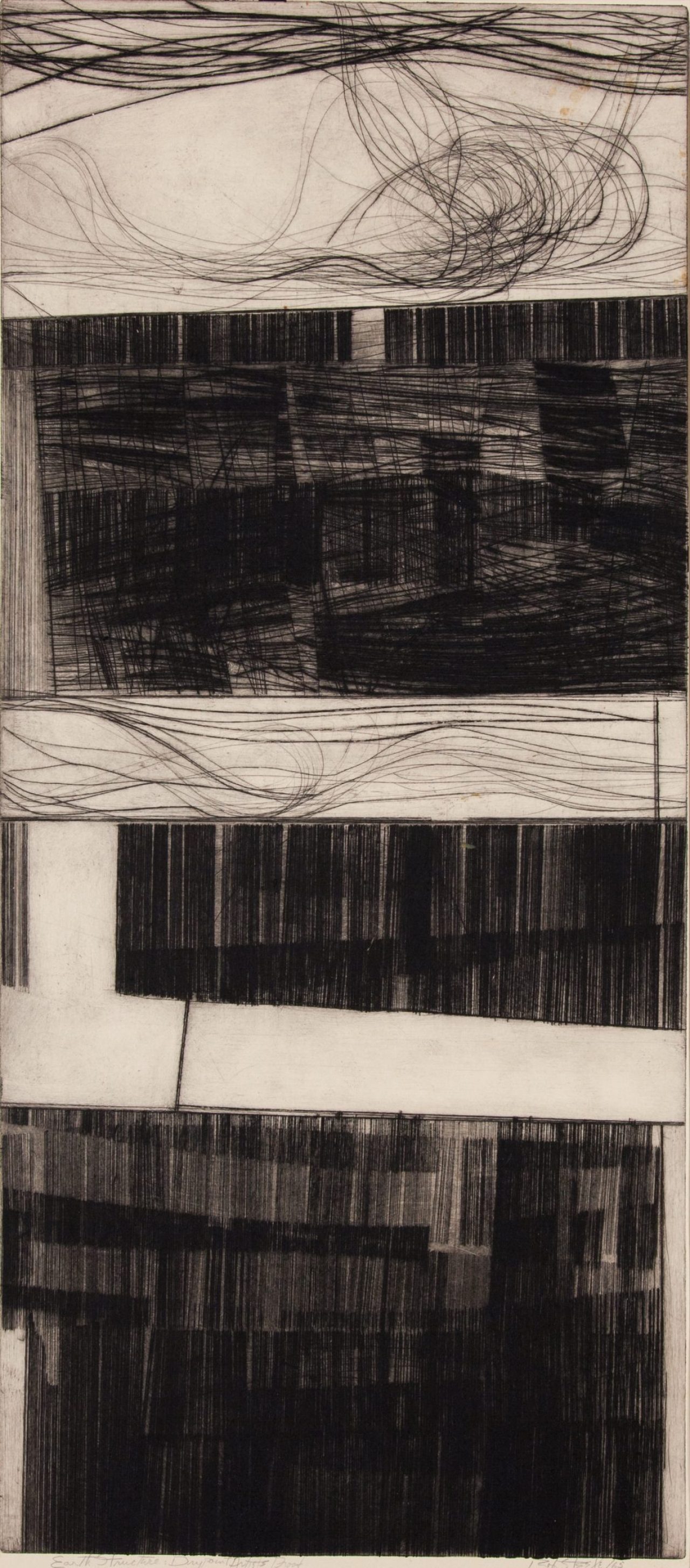

The drawings carry this with them; there is a vibrancy of layer and mark that makes them shimmer, lending a depth and translucency that seems to hold more than the marks of cross-hatched or dappled ink on paper. Looking slowly, over hours, days, years, the eye picks up things only the hand can translate: the slow uncurling of petals as a Higo iris blooms in the quiet midwinter light; the weight-born impression of a pistil as it rests against a broadleaf; the fluency of a vine’s winding through crevasse and crumbling mortar on the exterior of a building’s edge. Touch knows these sensations better than the eye does.

This act of translation, from the slow looking to the slow marking to the buildup over space and time, whether through the veins of a leaf, whippiness of a vine, or stamen of a flower’s head, brings a bodily quality to the drawings. There is a visceral sense there, but more so, it is a viscerality that asks to extend beyond the human. There are questions in the work: is this the gut feeling of a flower about to bloom? Is this the prickling-at-the-edges trepidation held by these vines as they cluster? What is the gentle sensation of light against the fine hairs of a stalk? Less so botanical drawings, Johnson considered these works portraits. Of her work, she writes:

“My attachment to flowers springs from my childhood and my mother’s beautiful English garden. Each species manifests unique characteristics within a sensual, natural, growth cycle. I observe the intrinsic visual properties of each, much as a portrait artist dwells on the character of each sitter. It is my hope that through slight stylized adjustments I might intimate both the natural inclination and the spatial context of each specimen.

Each drawing is, if you like, a proposal that the flowers unfold on the page in their own inimitable way, just as delicate and translucent bowl unfolds in the hand.”3

Johnson was better known as a potter, but let us not forget that both matter for clay and vitality for plants come from the earth.4 These are portraits not just of flora, but of the places they connect to, whether the roots spreading through the ground itself, or the sun soaking into leaves in the environments they grow in. She largely drew plants that originated elsewhere; transplants cultivated by and carried with people on their own journeys – whether for food, for medicine or for company. With them are stories of cultivation, and the way plants bend or change to the worlds of people as they are carried with, as wide ranging as across broad stretches of land and water, or as close as from the back garden to a pot on the studio window sill.

But these plants shape in turn. Many of the drawings possess an architectural quality, and at times, one referencing landscape; the plants are not passive subjects, nor passive in the worlds they inhabit and create. Some of her works are titled after sites shaping and shaped by these plants – referencing the places she observed, drew and marked through her travels. While she moved quickly between places, from Bernard Leach’s pottery studio in St. Ives, England to Tangiers, Morocco and Hawai’i, the touch of her eye to vegetation to hand kept her lingering over the same flowers as sitters for decades.

“…needed to go out and throw a few bowls and watch the white Higo iris bloom…”5

The slowing down in these works, and a commitment to vegetation and growing things, their worlds and their times, exists against the rhythms of life and time seen more frequently today. In any act of translation, from looking to feeling to marking, something of yourself is always translated in turn. This matters; which feelings feel, which marks mark, which worlds world.6 Johnson’s life held a dedication to the ways of pots, plants and materials born of the earth. These drawings ask and offer in turn, not only how these materials and sensations translate to the human, but how it might be to bend oneself to the worlds of flowers.

Works from the Collection considers works in the Belkin’s permanent collection in conversation with ongoing exhibitions, programs and the world around us. This entry is brought to you by Jay Pahre, Digital Publics Facilitator at the Belkin. He is a visual artist, writer and educator. To see more of the Belkin’s collection, visit belkin.ubc.ca/collection.

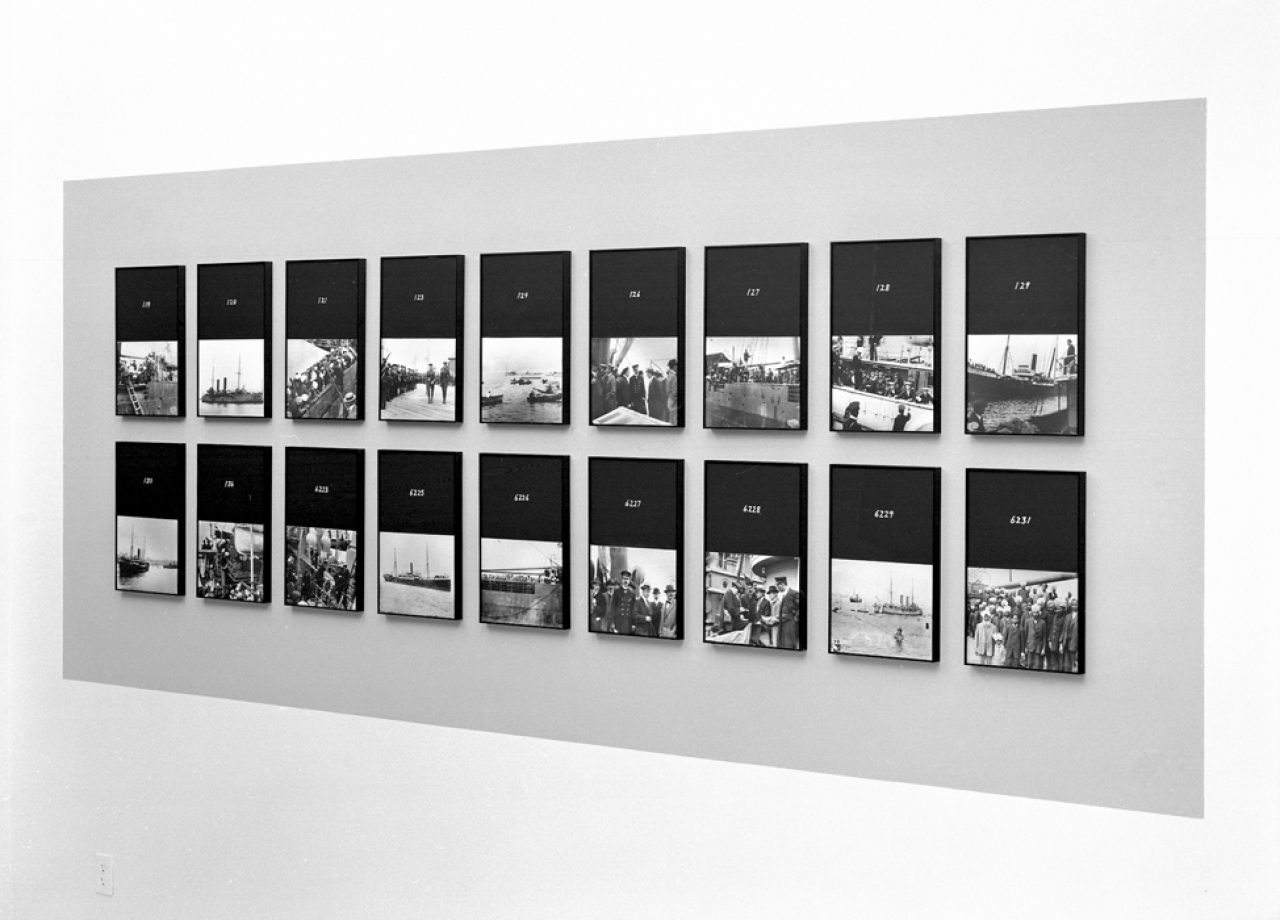

Image (above): Charmian Johnson’s Drawings, installed as part of The Willful Plot at the Belkin (13 January-16 April 2023). Photo: Rachel Topham Photography

-

Charmian Johnson

Charmian Johnson (Canadian, 1939-2020) was an artist and educator who lived and worked in Vancouver. She studied ceramics under Glenn Lewis, and developed a distinct style within the Leachian tradition having spent a number of years at Bernard Leach’s pottery studio in St. Ives where she catalogued and archived the Leach collection. Beginning in the 1970s, Johnson has been highly regarded across local and international ceramic communities. Throughout her lifetime, she developed a meticulous drawing practice that she kept largely to herself. Rendering botanical elements she encountered in her own garden as well as on her travels to Morocco, Turkey, Hawaii and France, Johnson developed her drawings over time, sometimes for months or even years. Johnson studied drawing, graphics and pottery at the University of British Columbia. She has had solo exhibitions at the Vancouver Art Gallery and UBC Fine Arts Gallery (now the Belkin Gallery). Johnson has been featured in group exhibitions across Canada, including the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; the UBC Museum of Anthropology, Vancouver; the Burnaby Art Gallery; the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria; the Glenbow Museum, Calgary; the Museum of Natural Sciences, Ottawa; Catriona Jeffries Gallery, Vancouver; and in the 2004 exhibition Thrown: Influences and Intentions of West Coast Ceramics at the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, which she co-curated.

Read More

End Notes

Charmian Johnson, email correspondence with Jana Tyner, July 3, 2013.

Ibid.

Charmian Johnson, “Artist’s Statement,” Charmian Johnson (Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 1989). Exhibition Pamphlet.

The history of botanical drawings in the west, and in particular settler colonial states such as British Columbia, is bound up with notions of science, discovery and progress emerging from colonial outlooks. For a brief introduction to this history in the context of botanical drawing in BC, see Plantae Occidentalis: 200 Years of Botanical Art in British Columbia by Maria Newberry House and Susan Munro (Vancouver: UBC Botanical Garden, 1979).

Charmian Johnson, email correspondence with Jana Tyner, June 19, 2013.

Referencing thinking from Donna Haraway’s “Staying with the Trouble” in On the Necessity of Gardening: An ABC of Art, Botany and Cultivation (Netherlands: Valiz, 2022).

Related

-

Exhibition

13 Jan – 16 Apr 2023

The Willful Plot

The Willful Plot brings together artists' practices to expand the notion of the garden as a site of tension between wild and cultivated, temporal and perpetual, public and private, sovereign and colonized. Here, the garden is considered by the artists not only as a delineated patch of earth, but as a story and a will to drive that story to complicate the way in which cultures and individuals see themselves in relation to ecology, sociality, belief and possibility. It is an opportunity to look at human relationships with land, flora, fauna and their interrelatedness. In its willfulness, the resistance garden is a counter-site, a heterotopia for alternative cultivation and potential transformation.

[more] -

Event

Wednesday, 12 Apr 2023 at 2 pm

Concert at the Belkin: The Willful Plot

Join us for a concert by the UBC Contemporary Players directed by Paolo Bortolussi and teaching assistant Ramsey Sadaka in a program that celebrates the Belkin’s current exhibition The Willful Plot.

[more] -

News

15 Dec 2022

Reading Room: The Willful Plot

The Willful Plot brings together artists’ practices to expand the notion of the garden as a site of tension between wild and cultivated, temporal and perpetual, public and private, sovereign and colonized. This online Reading Room includes texts expanding on different notions of the garden and more-than-human relationships, as well as the political implications of thinking willfully, with and alongside.

[more] -

Event

Wednesday 29 Mar 2023 at 1 pm

Lecture Series: What a seed does; or, tending to paradise, however you see it

Join us for a series of lectures at the Belkin. We invite Jane Wolff, Desirée Valaderes and Sara Jacobs to address The Willful Plot.

[more] -

Exhibition

30 January 2004 – 4 April 2004

Thrown: Influences and Intentions of West Coast Ceramics

This exhibition presented over 600 ceramics produced since the 1960s that were influenced by the studio pottery movement of Bernard Leach and Shoji Hamada. Betweeen 1920 and 1996, the Leach Pottery at St. Ives in Cornwall, England was a destination for some 100 apprentices and students from around the world who sought to integrate philosophic, aesthetic and moral ideals into the production of pottery. It has been one of the most significant influences in Western Europe and North American practice in the twentieth century.

[more] -

News

03 Mar 2021

Works from the Collection: Laiwan

Laiwan writes, "Begun in 1987 investigating the questions, What is an image? What is a photograph?, she who had scanned the flower of the world... is an ongoing project where I collect flowers from the city I am showing in, placing the petals into slide mounts."

[more] -

News

26 Jan 2021

Works from the Collection: Liz Magor

Liz Magor talks about the process of creating Tent (1999).

[more] -

News

19 May 2020

Works from the Collection: Roy Arden

Scott Watson considers Roy Arden's Komagata Maru as the City of Vancouver marks May 23 as the Komagata Maru Day of Remembrance.

[more] -

News

11 May 2020

Works from the Collection: Robert Steele

David Steele chooses a work by his late father, Robert Steele, that holds deep resonance for him.

[more] -

News

24 Jul 2020

Works from the Collection: Krista Belle Stewart

Karen Zalamea talks about Krista Belle Stewart's two-channel video, Seraphine, Seraphine (2015).

[more] -

News

19 Jan 2021

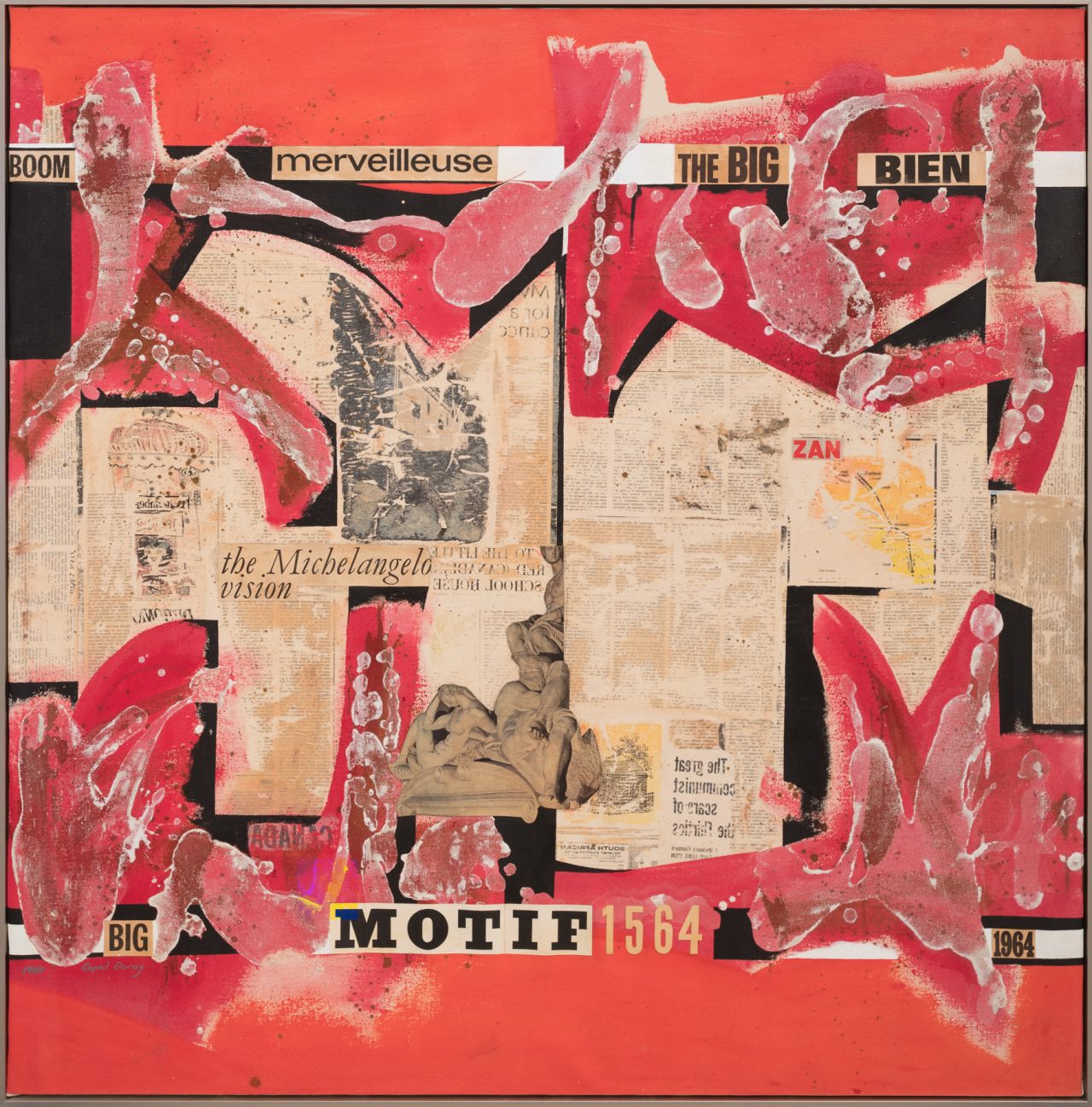

Works from the Collection: Audrey Capel Doray

[more]

[more] -

News

14 Apr 2020

Works from the Collection: Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller

Teresa Sudeyko talks about Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s 2001 House Burning.

[more] -

Exhibition

12 Jan – 3 May 2023

Outdoor Screen: Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller

From January until May 2023, the Belkin's outdoor screen will exhibit Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller's 3-minute video House Burning (2001) daily from 9 am until 9 pm.

[more]