30 Sep 2021

Online

National Day for Truth and Reconciliation

-

Beau Dick

ArtistChief Beau Dick (1955-2017), Walas Gwa’yam, was a Kwakwaka’wakw (Musgamakw Dzawada’enuxw First Nation) artist and activist who was acclaimed as one of the Northwest Coast’s most versatile and talented carvers. He was born in the community of Alert Bay, BC, and lived in Kingcome Inlet, Vancouver and Victoria before returning to Alert Bay to live and work. He began carving at an early age, studying under his father, Benjamin Dick, his grandfather, James Dick, and other renowned artists such as Henry Hunt and Doug Cranmer. He also worked alongside master carvers Robert Davidson, Tony Hunt and Bill Reid. In support of the Idle No More movement, Dick performed two spiritual and political copper-breaking ceremonies on the steps of the British Columbia legislature in Victoria in 2013, and on Parliament Hill in Ottawa in 2014. Dick created several important public works, including a transformation mask for the Canadian Pavilion at Expo 86 in Vancouver and the Ga’akstalas Totem Pole for Stanley Park, carved with Wayne Alfred and raised in 1991. His work has been shown in exhibitions locally and internationally, including Canada House, London, UK (1998); the 17th Biennale of Sydney, Australia (2010); documenta 14 in Athens, GR, and Kassel, DE (2017); and White Columns, New York (2019). He was the recipient of the 2012 VIVA Award and was artist-in-residence at the University of British Columbia’s Department of Art History, Visual Art and Theory from 2013 to 2017.

Read More

-

Skeena Reece

ArtistSkeena Reece (Tsimshian/Gitksan/Cree, b. 1974) is an artist based on the West Coast of British Columbia. Her installation and performance work has garnered national and international attention, most notably for Raven: On the Colonial Fleet (2010) presented at the 2010 Sydney Biennale as part of the group exhibition Beat Nation. Her multi-disciplinary practice includes performance art, spoken word, humour, “sacred clowning,” writing, singing, songwriting, video and visual art. She studied media arts at Emily Carr University of Art and Design, and was the recipient of the British Columbia Award for Excellence in the Arts (2012), the VIVA Award (2014) and the Hnatyshyn Award (2017). For Savage (2010), Reece won a Genie Award for Best Acting in a Short Film and the film won a Golden Sheaf Award for Best Multicultural Film, ReelWorld Outstanding Canadian Short Film, Leo Awards for Best Actress and Best Editing. Solo exhibitions include Surrounded at the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery (2019); Touch Me at the Comox Valley Art Gallery, Courtenay, BC (2018); Moss at Oboro Gallery, Montréal (2017) and The Sacred Clown & Other Strangers at Urban Shaman Contemporary Aboriginal Art, Winnipeg (2015). Group Exhibitions include Red on Red: Indigeneity, Labour, Value at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver (2022); Women & Masks: An Arts-Based Research Conference at Boston University (2021-22), Interior Infinite at the Polygon Gallery, North Vancouver (2021); Àbadakone at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa (2018-2019) and Sweetgrass and Honey at Plug In ICA, Winnipeg (2018), among others.

Read More

In observance of the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, the Belkin and the University of British Columbia are closed on 30 September 2021. This day is designated as an opportunity to “recognize and commemorate the legacy of residential schools.” It was originally proposed in 2015 by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, which under Action 80 called upon the federal government, in collaboration with Indigenous peoples, to establish a statutory holiday “to honour Survivors, their families and communities, and ensure that public commemoration of the history and legacy of residential schools remains a vital component of the reconciliation process.” With this in mind, the Belkin is sharing some suggested resources for education and advocacy, alongside two video works: the first work documents the late artist Beau Dick’s 2014 journey and copper-breaking ceremony on Parliament Hill in Ottawa; the second is Skeena Reece’s Touch Me (2013), which was part of the Belkin’s 2013 exhibition Witnesses: Art and Canada’s Indian Residential Schools.

Awalaskenis: Beau Dick’s Journey of Truth and Unity, 2014

Copper-breaking ceremony at Parliament Hill, Ottawa, 2014. Courtesy of Richard Anderson

On 2 July 2014, the late Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw artist Chief Beau Dick along with 21 companions set out from the University of British Columbia on a journey to Ottawa that they called Awalaskenis II: Journey of Truth and Unity. Intending to raise awareness about the plight of the environment and to challenge elected officials to attend to the relationship between the federal government and First Nations people, the group brought with them many objects including a copper shield known as Taaw made by Giindajin Haawasti Guujaaw, the Haida carver and former president of the Haida Nation. Guujaaw had encouraged Dick to make this journey, having been inspired by the 2013 Awalaskenis I journey from Quatsino on the northern tip of Vancouver Island to Victoria.

On 27 July 2014, the Taaw copper was broken on Parliament Hill in a traditional copper-breaking ceremony, marking a ruptured relationship in need of repair, and passing the burden of wrongs done to First Nations people from them to the Government of Canada. Once practised throughout the Pacific Northwest when copper shields were a symbol of justice and central to a complex economic system, this shaming rite had all but disappeared until Dick revived it in a similar ceremony in 2013 on the front steps of the British Columbia Legislature in Victoria. This earlier journey was instigated by Beau Dick’s daughters, Geraldine and Linnea Dick, as a way to bring the message of the Idle No More movement to the attention of the British Columbia government.

The Belkin worked with Beau Dick for the exhibition Lalakenis/All Directions: A Journey of Truth and Unity (16 January-17 April 2016) to document this journey through videos and photographs and to bring together the belongings and objects that became part of the journey to Parliament Hill.

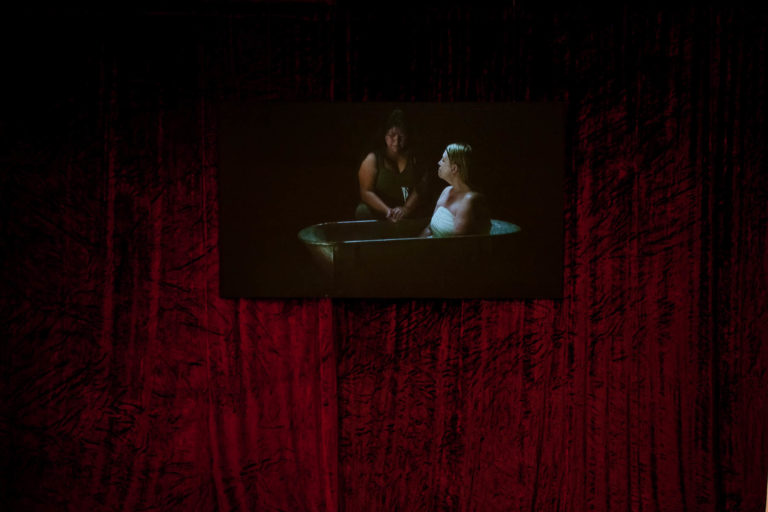

Skeena Reece, Touch Me, 2013

“The video Touch Me was my response to the curatorial intention of the 2013 exhibition Witnesses: Art and Canada’s Indian Residential Schools at the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery. Imagine your voice being included in such an important group show amongst artists you’ve known and loved: Rebecca Belmore, Beau Dick and Sandra Semchuk to name a few. What an honour. What a huge responsibility. I am a second generation residential school survivor and the effects of this phenomenon go deep. This is how I approach a lot of difficult subjects. I make art in place of my voice that wavers, stutters confusedly and reaches for the words that are too big to mouth.”

“The opening scene is a dark room with a well-lit tub. Sandra Semchuk and I approach the tub. I extend my hand to help her get into it. The cameras are set wide and a second cameraman follows our movements closely. Without speaking I bathe her gently, her hands, her face and pour water over her with a small copper pot. We do this for several minutes and eventually break our silence with a short dialogue where we shed some tears. My bathing Sandra is a gesture of care. Showing the ability to love, to respect and take care of others. From one generation to another, junior artist to senior artist and native woman to white woman. My response to this painful history is to share the continued ability to show reverence, respect, care, and love. Not despite our colonial history, but as a continuation of this strength that has been passed on since time immemorial. Speaking to my people I am saying that these abilities are not lost on me. Speaking to others I am saying this is ‘our’ resilience. I believe the context of the first showing informed how the work was received. This video was shown at the end of a long walk through a broad range of works addressing the effects of residential school. There was a bench to sit and rest. The images in the video are a welcome sight. Gentle.”

Skeena Reece, from Touch Me exhibition catalogue, Comox Valley Art Gallery, 2018.

Learn More and Engage

Witnesses: Art and Canada’s Indian Residential Schools exhibition catalogue, 2013

Lalakenis/All Directions: A Journey of Truth and Unity exhibition catalogue, 2016

Orange Shirt Day 2021 at the Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre

Sound House: Never Forgotten at the Museum of Anthropology

Intergenerational March to commemorate Orange Shirt Day

6 Ways to Deepen Your Understanding of Indian Residential School History by Carolyn Ali

Images (from above): Beau Dick at Parliament Hill, Ottawa, 2014. Photo: Sue Heel; Skeena Reece, Touch Me, 2013. Photo: Michael R. Barrick

-

Beau Dick

ArtistChief Beau Dick (1955-2017), Walas Gwa’yam, was a Kwakwaka’wakw (Musgamakw Dzawada’enuxw First Nation) artist and activist who was acclaimed as one of the Northwest Coast’s most versatile and talented carvers. He was born in the community of Alert Bay, BC, and lived in Kingcome Inlet, Vancouver and Victoria before returning to Alert Bay to live and work. He began carving at an early age, studying under his father, Benjamin Dick, his grandfather, James Dick, and other renowned artists such as Henry Hunt and Doug Cranmer. He also worked alongside master carvers Robert Davidson, Tony Hunt and Bill Reid. In support of the Idle No More movement, Dick performed two spiritual and political copper-breaking ceremonies on the steps of the British Columbia legislature in Victoria in 2013, and on Parliament Hill in Ottawa in 2014. Dick created several important public works, including a transformation mask for the Canadian Pavilion at Expo 86 in Vancouver and the Ga’akstalas Totem Pole for Stanley Park, carved with Wayne Alfred and raised in 1991. His work has been shown in exhibitions locally and internationally, including Canada House, London, UK (1998); the 17th Biennale of Sydney, Australia (2010); documenta 14 in Athens, GR, and Kassel, DE (2017); and White Columns, New York (2019). He was the recipient of the 2012 VIVA Award and was artist-in-residence at the University of British Columbia’s Department of Art History, Visual Art and Theory from 2013 to 2017.

Read More

-

Skeena Reece

ArtistSkeena Reece (Tsimshian/Gitksan/Cree, b. 1974) is an artist based on the West Coast of British Columbia. Her installation and performance work has garnered national and international attention, most notably for Raven: On the Colonial Fleet (2010) presented at the 2010 Sydney Biennale as part of the group exhibition Beat Nation. Her multi-disciplinary practice includes performance art, spoken word, humour, “sacred clowning,” writing, singing, songwriting, video and visual art. She studied media arts at Emily Carr University of Art and Design, and was the recipient of the British Columbia Award for Excellence in the Arts (2012), the VIVA Award (2014) and the Hnatyshyn Award (2017). For Savage (2010), Reece won a Genie Award for Best Acting in a Short Film and the film won a Golden Sheaf Award for Best Multicultural Film, ReelWorld Outstanding Canadian Short Film, Leo Awards for Best Actress and Best Editing. Solo exhibitions include Surrounded at the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery (2019); Touch Me at the Comox Valley Art Gallery, Courtenay, BC (2018); Moss at Oboro Gallery, Montréal (2017) and The Sacred Clown & Other Strangers at Urban Shaman Contemporary Aboriginal Art, Winnipeg (2015). Group Exhibitions include Red on Red: Indigeneity, Labour, Value at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver (2022); Women & Masks: An Arts-Based Research Conference at Boston University (2021-22), Interior Infinite at the Polygon Gallery, North Vancouver (2021); Àbadakone at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa (2018-2019) and Sweetgrass and Honey at Plug In ICA, Winnipeg (2018), among others.

Read More

Related

-

Exhibition

6 September 2013 – 1 December 2013

Witnesses: Art and Canada’s Indian Residential Schools

Witnesses: Art and Canada’s Indian Residential Schools presents artists who have produced work arising from the history of Indian Residential Schools in Canada and coincides with, but is independent from, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada National Event that will take place in Vancouver from September 18 to 21, 2013. The exhibition features artists from British Columbia and across Canada, and is cross-generational to include those who directly experienced Indian Residential Schools as well as those who are witnesses to its ongoing impact.

[more] -

Exhibition

16 January 2016 – 17 April 2016

Lalakenis/All Directions: A Journey of Truth and Unity

On July 2, 2014, renowned Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw artist Chief Beau Dick along with 21 companions set out from the University of British Columbia on a journey to Ottawa which they called Awalaskenis II: Journey of Truth and Unity. Intending to raise awareness about the plight of the environment and to challenge elected officials to attend to the relationship between the federal government and First Nations people, the group brought with them many objects including a copper shield known as Taaw made by Giindajin Haawasti Guujaaw, the Haida carver and former president of the Haida Nation. Guujaaw had encouraged Dick to make this journey, having been inspired by the 2013 Awalaskenis I journey from Quatsino on the northern tip of Vancouver Island to Victoria.

[more]