03 Aug 2021

Celebrating the Belkin’s 25th Anniversary

June 2020 marked the 25th anniversary of the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery. We had hoped to celebrate this significant occasion and honour the Belkin Family, the gallery’s architect Peter Cardew, and Scott Watson, who was due to step down at the end of June. But on March 17, 2020, the Belkin closed its doors – as did the rest of UBC and gradually much of the world – with the COVID-19 pandemic.

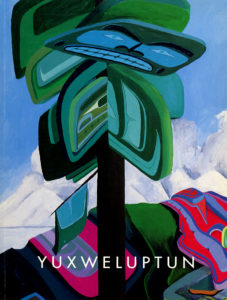

And so at this time, now more than a year later in 2021, we would like to remember and acknowledge the generosity of Dr. Helen Belkin and her family who gifted the funds to build the gallery. The Belkin opened in June 1995 with an exhibition of work by Salish artist Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun, preceded by a dedication by Musqueam Elder Dr. Vincent Stogan who welcomed guests to the Musqueam territory. At this opening, Dr. Belkin remarked that the new gallery celebrated the vision that her late husband Morris Belkin and former UBC President Norman MacKenzie shared – that one day there would be a fine arts precinct at the north end of campus dedicated “to promote discussion and understanding of contemporary art.” Dr. Belkin was also responsible for the establishment of permanent endowments at UBC that support our curatorial activities, art purchases, as well as lectures and symposia.

We are sincerely grateful for the continued support of the Belkin family and the Morris and Helen Belkin Foundation, and share now a video created especially for the 25th anniversary with reflections on the Belkin from Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun, Judy Radul, Stan Douglas, Jay Pahre, Scott Watson and Santa Ono, alongside writing from Scott Watson and Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun that reflects on this history.

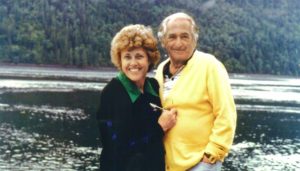

Lives Lived: Helen Hahn Harmer Belkin by Scott Watson

A woman noted for her generosity of spirit and wide circle of friends of many generations and walks of life, Helen Belkin (March 22, 1919-January 28, 1997) was an extraordinary woman. Her grace, kindness and rare powers of empathy affected everyone who knew her. When the University of British Columbia gave her an honorary doctorate in 1990 it was to recognize the contributions of a key player – and one of the last survivors – of the university’s golden age. That age was the 1950s, when humanist ideals and modernist optimism guided the expansion of Western Canada’s largest campus.

A woman noted for her generosity of spirit and wide circle of friends of many generations and walks of life, Helen Belkin (March 22, 1919-January 28, 1997) was an extraordinary woman. Her grace, kindness and rare powers of empathy affected everyone who knew her. When the University of British Columbia gave her an honorary doctorate in 1990 it was to recognize the contributions of a key player – and one of the last survivors – of the university’s golden age. That age was the 1950s, when humanist ideals and modernist optimism guided the expansion of Western Canada’s largest campus.

A woman noted for her generosity of spirit and wide circle of friends of many generations and walks of life, Helen Belkin (March 22, 1919-January 28, 1997) was an extraordinary woman. Her grace, kindness and rare powers of empathy affected everyone who knew her. When the University of British Columbia gave her an honorary doctorate in 1990 it was to recognize the contributions of a key player – and one of the last survivors – of the university’s golden age. That age was the 1950s, when humanist ideals and modernist optimism guided the expansion of Western Canada’s largest campus.

A woman noted for her generosity of spirit and wide circle of friends of many generations and walks of life, Helen Belkin (March 22, 1919-January 28, 1997) was an extraordinary woman. Her grace, kindness and rare powers of empathy affected everyone who knew her. When the University of British Columbia gave her an honorary doctorate in 1990 it was to recognize the contributions of a key player – and one of the last survivors – of the university’s golden age. That age was the 1950s, when humanist ideals and modernist optimism guided the expansion of Western Canada’s largest campus.

Helen was born on March 22, 1919 at Vancouver General Hospital. Her father, Alton Stuart Hahn, who had moved to the west coast from Harbour Buffet, NF in 1917, was a Detective Inspector with the Vancouver Police. Her, mother, Ada Jane Alexander, was from a Presbyterian Ontario farming family. Helen grew up in Vancouver’s working-class east side, moving to Point Grey after Helen graduated from Britannia Senior Secondary in 1936.

Much of Helen’s strength of character and compassion was shaped by the Depression years. Her father had a secure job, but he opened his house to homeless men who came looking for work in exchange for a meal. The images and memories of these men stayed with her all her life.

She met her first love and husband to be, Jim Harmer, in Gordon Shrum’s physics class in her first year at UBC. Harmer was a star athlete, captaining both the Varsity hockey and football teams. They must have been a striking couple. Helen became president of her sorority, Alpha Gamma Delta. Her connection with the sorority was lifelong and she served as president of the alumni chapter and head of pledge training.

After she graduated with a BA in English and History and completed teacher training, Helen took her first professional job at Ladner Secondary where she taught English, Commercial (typing and shorthand) and, absurdly she thought, the boy’s Physical Education class.

Helen married Jim Harmer in the spring of 1942. He was by then a lieutenant in the Canadian Army and posted at Truro, NS. They rendezvoused in Toronto and honeymooned for a week in Niagara Falls before Jim’s return to duty. In November of that same year Helen gave up her teaching job and went to start married life with Jim in Camp Borden, Barrie, ON. When Jim left for overseas combat eight months later, Helen was expecting her first child.

She was back in Vancouver, living with her widowed mother and her new child when she heard that Jim Harmer was missing in action in France. At twenty-five, Helen was a single mother.

When she heard her old physics teacher, Gordon Shrum, who was now Dean of Science at UBC, was looking for a secretary, she applied. As her son, Stuart Belkin, delicately put it in his eulogy to her, Helen had an ability to deal with demanding men. With Shrum, she organized the accommodation of service men returning to university after the war.

When Norman MacKenzie became President of UBC in 1946, he wanted the ablest executive secretary on campus and that was Helen Harmer. It was under MacKenzie that the Schools of Architecture and Music and Departments of Theatre and Fine Arts were all established. Helen worked for MacKenzie for eight years. Her daughter, Sharon, remembers Saturdays and evenings playing in the administration office while Helen oversaw the logistics of these and other new projects.

She met Morris Belkin, a vital and soon-to-be highly successful industrialist at the Hadassah Bazaar in 1953. He was smitten with this attractive and independent woman and must have counted himself the luckiest man alive when she agreed to marry him eight months later. Helen gave up her university career to preside over a family of five (Morris had two young sons from a previous marriage). Within three years the family grew to eight.

Helen flourished in the hectic environment of the Belkin household, supporting the activities of five children as well as her husband’s growing business. A gracious and elegant hostess, she more than once responded to Morris’s five o’clock call announcing he was bringing important clients home for dinner. Helen was instrumental in the rise of Belkin Paper Box to be the largest paper packaging company in Canada seeing it go from a small concern with a handful of employees to an outfit that employed thousands. As her children grew, Helen had more time for charity work and held campaign positions with the United Way and the Junior League.

Helen flourished in the hectic environment of the Belkin household, supporting the activities of five children as well as her husband’s growing business. A gracious and elegant hostess, she more than once responded to Morris’s five o’clock call announcing he was bringing important clients home for dinner. Helen was instrumental in the rise of Belkin Paper Box to be the largest paper packaging company in Canada seeing it go from a small concern with a handful of employees to an outfit that employed thousands. As her children grew, Helen had more time for charity work and held campaign positions with the United Way and the Junior League.

The pace of the Belkin household came to a sudden slowdown in 1985 when Morris suffered a serious stroke. He died in 1987. Helen herself became afflicted with severe arthritis in middle-age. Throughout all adversity, Helen met life with unflagging faith and goodwill.

In 1988, Helen approached UBC with a proposal to build a new art gallery. As a major patron she was exemplary and made all of us at UBC feel like we were giving her a gift rather than receiving one. After the Morris and Helen Art Gallery opened in 1995, Dr. Belkin and her family further endowed an operating fund.

At the memorial service, I met a woman who had grown up knowing the Belkins. For her and for many young women and men in Vancouver, Helen had been an inspiring model and friend who taught others that life’s greatest rewards come from family and service to the community.

An abridged version of this text was published as “Lives Lived: Helen Hahn Harmer Belkin,” Globe and Mail, April 1, 1997.

Born to Live and Die on Your Colonialist Reservations by Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun

CONCENTRATION CAMPS = RESERVATIONS

CONCENTRATION CAMPS = RESERVATIONS

RESERVATIONS = SEGREGATION

SEGREGATION = INTERNMENT CAMPS

INTERNMENT CAMPS = THE INDIAN PROBLEM = THE INDIAN ACT

I suppose that if I am to talk about my work, I will have to start with the past. By 1900 the genocide of First Nations people, the plagues, the massacres, murders and wars, left over 100 million victims dead – nations, tribes, villages, families. Concurrently the Great Land Grab was on. Colonial racist views considered natives as bestial rather than human, as uncivilized savages without social organization or means by which to govern themselves. I call this the Amnesiac Colonial Collective Denial Credo Ideology.

CONCENTRATION CAMPS = RESERVATIONS

CONCENTRATION CAMPS = RESERVATIONS

RESERVATIONS = SEGREGATION

SEGREGATION = INTERNMENT CAMPS

INTERNMENT CAMPS = THE INDIAN PROBLEM = THE INDIAN ACT

I suppose that if I am to talk about my work, I will have to start with the past.

By 1900 the genocide of First Nations people, the plagues, the massacres, murders and wars, left over 100 million victims dead – nations, tribes, villages, families. Concurrently the Great Land Grab was on.

Colonial racist views considered natives as bestial rather than human, as uncivilized savages without social organization or means by which to govern themselves. I call this the Amnesiac Colonial Collective Denial Credo Ideology.

This ideology of denial was ingrained in the mandate of the church, the government and the military. Its first sign was the simple act of Europeans jumping off a boat, flag in hand, and laying claim to “said land.”

European intervention into “New World” territories included treaties based on a Nation-to-Nation position. However, through time, prudent politicians began to deconstruct First Nations governments. Nation by Nation, territory by territory, destroying the foundation of said First Nations. From henceforth I accuse the said Crown and government officials of perjury in the first degree. Living under this despotism First Nations peoples have always sought an honourable settlement of the said land, British Columbia.

European intervention into “New World” territories included treaties based on a Nation-to-Nation position. However, through time, prudent politicians began to deconstruct First Nations governments. Nation by Nation, territory by territory, destroying the foundation of said First Nations. From henceforth I accuse the said Crown and government officials of perjury in the first degree. Living under this despotism First Nations peoples have always sought an honourable settlement of the said land, British Columbia.

Land claims have always concerned me: fishing rights, hunting rights, water rights, inherent rights. My home, my native land. Land is power, power is land. This is what I try to paint.

Native people have endured too many years in forced concentration camps in BC. The Department of Indian Affairs has been unsparing of time and lawyerly energies in maintaining a despotism that is backed up by the RCMP, the Canadian army, Canadian airforce, Canadian coast guard, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, game wardens, provincial courts and the Supreme Court of Canada.

Land is far more important than taking monetary wealth from the outlanders. I am tired of your usufructuary rights, I am fed up of being a usufruct person. I am tired of being fruct around by all of you. I would like to see all First Nations people have self-government and be able to protect their rights as aboriginal people.

I work from the native perspective that all shapes and any elements can be changed to anything to present a totally native philosophy. It allows me to express my feelings freely and show you a different view.

I find that it is very important to record the times in which I live. We all have to live from this land. Your children’s children and my children’s children will have to live together. The land, this is everyone’s responsibility now, so that their hopes and dreams, their future, can be protected. I hope my children will never have to experience hate and racism just because of the colour of their skin. Respect the land and care for it. I love this land and hope you can understand all the feeling I have for it because it is all I have to share.

At this point, I would like to thank all the teachers I have had, including my Dad, who said to me one day: “Lawrence, be proud of who you are. Take pride in what you do and do not dishonour me, my son.”

This artist statement appeared on the gallery wall during the Belkin’s inaugural exhibition, Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun: Born to Live and Die on Your Colonialist Reservations (June 20-September 16, 1995).

Remembering Dr. Vincent Stogan

On behalf of the Musqueam Nation, Dr. Vincent Stogan Tsimilano welcomed guests to his homeland and offered an official dedication at the opening of the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, Wednesday, June 14, 1995. Born to a family of healers, chiefs and elders, Vincent Stogan (1918-2000) received his traditional Musqueam education from his grandfather, his father, his older brother and other Musqueam elders.

On behalf of the Musqueam Nation, Dr. Vincent Stogan Tsimilano welcomed guests to his homeland and offered an official dedication at the opening of the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, Wednesday, June 14, 1995. Born to a family of healers, chiefs and elders, Vincent Stogan (1918-2000) received his traditional Musqueam education from his grandfather, his father, his older brother and other Musqueam elders.

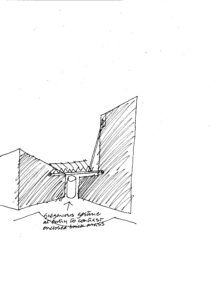

Pivotal Design: Peter Cardew

It is a pleasure to recall working with Peter Cardew on the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery at the University of British Columbia, which opened in June of 1995. We chose Peter for two reasons. Firstly, we liked his commitment to his Modernist ideas. In the early nineties, Postmodernism’s sway had not quite yet expired. Peter exemplified the ethical, philosophical and political understanding of architecture that we call Modernism. Secondly, alone among the shortlisted candidates, Peter was prepared to talk about specific new gallery spaces he had visited and thought about.

It is a pleasure to recall working with Peter Cardew on the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery at the University of British Columbia, which opened in June of 1995. We chose Peter for two reasons. Firstly, we liked his commitment to his Modernist ideas. In the early nineties, Postmodernism’s sway had not quite yet expired. Peter exemplified the ethical, philosophical and political understanding of architecture that we call Modernism. Secondly, alone among the shortlisted candidates, Peter was prepared to talk about specific new gallery spaces he had visited and thought about.

The design process took over two years. The building design went through much iteration as Peter thought through the responses of the committee. He consistently managed to find eloquent and sensitive solutions to design requests that were sometimes not fully articulated. Peter was particularly adept at handling the bureaucratic process at UBC. The University was an especially difficult client in those days – it had decided on a kind of Brutalist Gothic in pinkish brick as its standard look for the Main Mall. Besides our own committee, Peter had to meet with another committee that rarely communicated with ours. It was this committee which had the power to give or withhold the final approval of the design and, as I recall, there was resistance. Among the many issues that arose at the final design stage was the roof (Why couldn’t it be flat? Wouldn’t that be cheaper?). I accompanied Peter once to the other committee where he was asked, as a challenge to the design’s supposed lack of a clear “façade,” to name a building without a façade as a precedent. Without hesitation he replied, “The Coliseum.” To the suggestions that some trees “hugging” the building might mitigate the severity of its elevations, he replied dryly, “Hugging?” Peter prevailed with unfailing charm, patience and level-headedness. He also had the support of the donor – Helen Belkin – for his design. That helped a great deal.

The design process took over two years. The building design went through much iteration as Peter thought through the responses of the committee. He consistently managed to find eloquent and sensitive solutions to design requests that were sometimes not fully articulated. Peter was particularly adept at handling the bureaucratic process at UBC. The University was an especially difficult client in those days – it had decided on a kind of Brutalist Gothic in pinkish brick as its standard look for the Main Mall. Besides our own committee, Peter had to meet with another committee that rarely communicated with ours. It was this committee which had the power to give or withhold the final approval of the design and, as I recall, there was resistance. Among the many issues that arose at the final design stage was the roof (Why couldn’t it be flat? Wouldn’t that be cheaper?). I accompanied Peter once to the other committee where he was asked, as a challenge to the design’s supposed lack of a clear “façade,” to name a building without a façade as a precedent. Without hesitation he replied, “The Coliseum.” To the suggestions that some trees “hugging” the building might mitigate the severity of its elevations, he replied dryly, “Hugging?” Peter prevailed with unfailing charm, patience and level-headedness. He also had the support of the donor – Helen Belkin – for his design. That helped a great deal.

In the end, I can say that the building is a pleasure for those who work in it, exhibit in it and visit it. Peter’s white glazed brick triumphed over the threat of pink brick because it tied the buildings to the nearby Lasserre and Buchanan Buildings, making a statement about the coherence of the Norman MacKenzie Centre for Fine Arts.

Previously, the gallery had been housed in the basement of a (now demolished) wing of the University’s Main Library (now the Barber Learning Centre) where our offices were adjacent to the exhibition space. A window next to the entrance hall meant that we could monitor the gallery without a guard while we worked in our offices. We were always connected to the exhibition space and our visitors. Sometimes, we even conversed with them. Importantly, it was a way of watching our visitors interact with the exhibitions. Peter’s solution to this challenge was the overall openness of the interior of the Belkin, where the offices were located on an open mezzanine overlooking the gallery entrances.

The idea behind the main gallery was to make it not at all precious so that holes cut through walls or even in the cement floor could be repaired easily. Pivoting walls were basically configured in four ways – at least that was Peter’s instruction to us. He did not envision us using the pivoting walls diagonally. But after a while we did, and found that the space was even more flexible than he had initially planned. After 17 years and over 70 exhibitions, I can say that the pivoting walls function very well. Invariably, shows on tour look their best inside the Belkin. The gallery is a pliable and hardy instrument that can be adapted to many circumstances. It is a very convincing argument for the white cube. Importantly, the building is open to discovering new ways of using it.

Rather astonishingly, the Belkin Art Gallery was the only freestanding purpose-built art gallery in the Lower Mainland when it was constructed. It still is.

This text was originally published in “RAIC Gold Medal 2012: Peter Cardew,” Canadian Architect 56:6 (June 2012): 23-25.